There is a passage in Thucydides’ Peloponnesian War, Book II, §§60-63, in which Pericles defends his war policy. In most respects it is an unremarkable speech. The fact that it found on Pericles’ lips is unremarkable. It could be Lyndon Baines Johnson, or Richard Milhous Nixon, or Ronald Reagan, or George Bush, or — now — Barrack Hussein Obama. We are all familiar with the speech. Sons, fathers, uncles, brothers have been returning home in body bags. The wages of war are everywhere. Disease, unsanitary conditions, fear, despair. And, so, quite understandably the families whose loved ones are dying begin to question the wisdom of war. And so Pericles steps up and addresses his detractors:

I expected this outbreak of anger on your part against me, since I understand the reasons for it; and I have called an assembly with this object in view, to remind you of your previous resolutions and to put forward my own case against you, if we find that there is anything unreasonable in your anger against me and in your giving way to your misfortunes. . . . As for me, I am the same as I was, and do not alter; it is you who have changed. What has happened is this: you took my advice when you were still untouched by misfortune, and repented of your action when things went badly with you; it is because your own resolution is weak that my policy appears to you to be mistaken. . . . And do not imagine that what we are fighting for is simply the question of freedom or slavery: there is also involved the loss of our empire and the dangers arising from the hatred which we have incurred in administering it. Nor is it any longer possible for you to give up this empire, though there may be some people who in a mood of sudden panic and in a spirit of political apathy actually think that this would be a fine and noble thing to do. Your empire is now like a tyranny: it may have been wrong to take it; it is certainly dangerous to let it go (1974:158-161).

Among the multiple overlapping inconveniences of empire is the danger entailed by withdrawing garrisoned troops from conquered lands. Here, the Athenians alone seem to have been deluded into believing that the colonized appreciate the colonizers. Which is not to say that the conditions of the colonized changed dramatically with the arrival of Athenian troops. For the past three days, my sons and I spent time in Budva, Montenegro, a seaside resort now mostly occupied by Russian tourists and developers, less than two hundred kilometers north of Durrës, Albania, where the Peloponnesian War began. Then named Epidamnus, this city state was a colony of Corcyra (the present day island of Kerkira, just down the coast). Naturally enough, when the Epidamnians overthrew their aristocratic rulers and declared themselves a democracy, they anticipated that fellow democrat, Pericles, down in Athens, would be overjoyed. Instead, Pericles took sides with the ousted aristocrats, compelling the Epidamnians to seek assistance from Sparta’s ally, Corinth. And so the war began.

In all likelihood, the Epidamnians were no worse under Athenian occupation than under Corcyrian occupation. Occupation is occupation. War is war. Yet, among the conceits the Athenians entertained was that the peoples subject to Athenian occupation actually preferred occupation by the free people of Athens than subjection under their own oligarchs. And we know exactly why they entertained this conceit. Pericles himself had cultivated it in his many speeches praising the Athenians for their emancipatory mission throughout the Pelopponese. Was Pericles himself deluded? Of course not. And here Thucydides gives us a rare glimpse at the cynicism that bristles within every imperial ruler. Pericles knew quite well that the moment Athens withdrew her (meaning Athena’s) troops, all hell would break lose. And he evidently also had some inkling that “it may have been wrong to take it,” meaning seizing Athens’ colonies. He even apparently knew that Athens itself was not a democracy, as he noisily proclaimed on many occasions, but a tyranny.

A headline in today’s New York Times reads “Obama Finds He Cannot Put Iraq War Behind Him.” No, he cannot. And no one doubts, I hope, that when Obama refuses to send more troops into Iraq the Republicans in Congress will have a field day blaming him for losing the war that they had won. “It may have been wrong to take it; it is certainly dangerous to let it go.” Yet, let it go he must. Just as the US must commit itself to closing down and withdrawing its troops from all of its outposts around the world. Dangerous? Yes. But the greatest danger will not come from the peoples in the nations the US currently occupies. It will come from the people back home, who ever since the 1980s have been noisily fed the self-contradictory lie, Memorial Day after Memorial Day, both that “they” invited us to preserve “their freedom,” and that the reason we are “over there” is to prevent “them” from coming “over here.” Clearly these contradictory justifications for unlawful war and occupation cannot both be true.

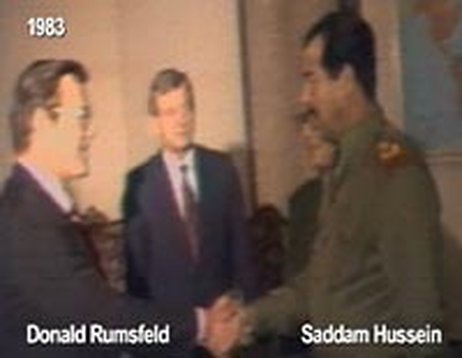

And few photographs more clearly illustrate which of these statements is more true than Secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s shaking hands with Saddam Hussein.

Are we so naive as to believe that empires have no enemies or that they need not maintain defensive troops? No. But just as Pericles was ready to acknowledge that Athens had become a tyranny and that it was probably wrong for her to economically and militarily dominate her neighbors, so it is high time that Americans shed the illusion that the world cheers our military presence in their midst. It will be dangerous for us to withdraw, everywhere and anywhere, because we have won the wrath of the communities we occupy. But the real danger comes from those many Americans who have drunk the Kool Aid served them daily in our pay-for-service media by our pay-for-service political leaders. I hear them already decanting into the Republican Party.