War breaks out wherever we human beings live (http://nyti.ms/1EZz7xa). We might wish that it avoided spaces that for us have historical value. But we might also wonder what that value is.

As Palmyra fell to the militants known as the Islamic State, my first response not simply as a historian, but as a human being, was remorse. My second response was: well, of course. Human beings live there. Therefore there is war. But, again, as a historian, I know that that response is unsatisfactory. After all, I also live where human beings live; and war has not broken out here; well, not at least since World War II. And, even then, its only signs were bunkers fixed with big guns and huge internment camps filled with Japanese (and a few other Asians for good measure). Obviously the presence of human beings is no guarantee for war.

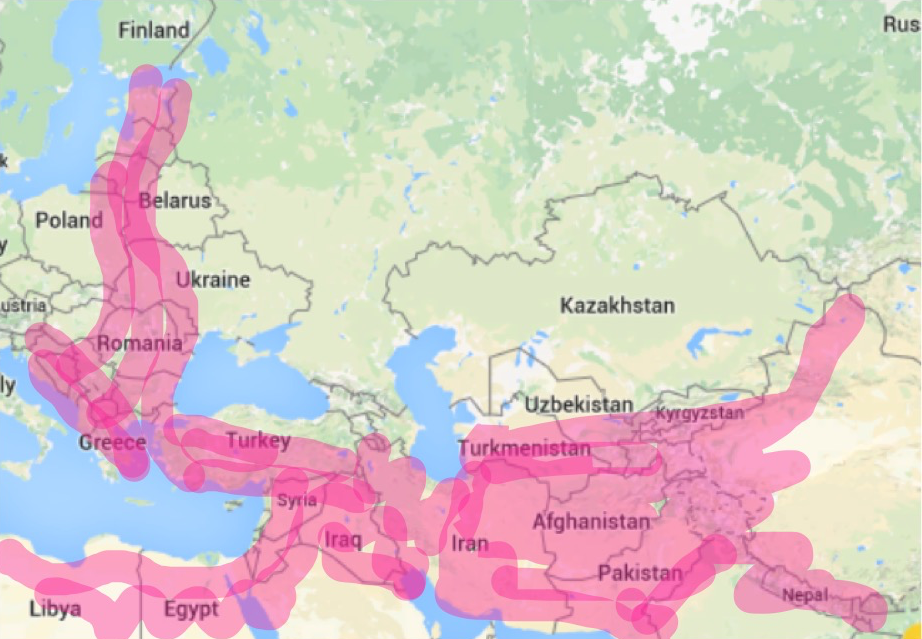

No, war breaks out where territory is contested. And nowhere has this contest been more fierce than along the seam that runs from the Baltics down through Central and Eastern Europe and then fans out southward into northern Africa and eastward into western China, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Without pretending scientific precision, the map looks something like so:

It covers a territory that includes Omar Bartov and Eric D. Weitz’s “Shatterzone” (the German, Habsburg, Russian, and Ottoman borderlands), but clearly it extends further south than this map shows, and further east. Also, it is connected less to the German, Habsburg, Russian, and Ottoman empires than to the efficiencies that present-day empires or fiefdoms are attempting to extract from the rents they can charge on the commodities that can be extracted along this seam. People live here and there is war. But what is bringing this seam to unravel (“shatter,” in my view, is too abrupt and insufficiently nuanced) is that we do not live there. Rather, we benefit from the commodities and rents that somehow found themselves onto and beneath the soil of these lands.

We are in a bind. As the efficiencies we are able to extract from our own lands and peoples reach their margins, we have had to search elsewhere for those efficiencies that remain. I am not only thinking here of oil extraction and refining, though of course this is central. I am also thinking of the huge, largely untapped labour resources that populate this region. If you have not listened lately, you might eavesdrop on a couple of Defense Department briefings. Everything is now about training local people — in Iraq, in Pakistan, in Afghanistan, in Syria, in Ukraine — to fight their own wars. But why? What are they fighting for? For whom are they fighting? Against whom?

Last year, our family lived in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina, less than an hour from the Serbian border. And we experienced first-hand the large number (up to 50%) of young men and women recruited by private military subcontractors to service the US military and allies in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is dangerous work for pay that few US citizens would accept. And, yet, so desperate are the circumstances of young adults in the Balkans (where unemployment hovers between 50 and 75% and where the minimum wage is roughly 2€/hr) that they are more than willing, even eager, to risk their lives if it holds the potential of future marriage, a home, and a car. Now that’s efficiency!

Ultimately, what policy-makers are hoping for are counter-insurgency campaigns sufficiently robust to realize efficiencies all across this seam, suppressing local and regional uprisings of communities that no longer wish to endure the indignities of client status to the empires or princes who crave the efficiencies promised by their labour and land.

For the families of Palmyra, this is nothing new. Before being annexed by the expanding Roman Empire, the Palmyrans lived under the domination of the Seleucid dynasty. Their fair city then transferred in an unbroken chain to the Byzantines, the Rashiduns, the Ummayads, the Abbasids, and the Mamluks before catching its breath under the Ottomans. In 1918 Versailles gave Palmyra to the Syrians (i.e., the French). The French vacated in 1946, which is when the oligarchs commenced their internecine war for domination, eventually resulting in the victory of Ba’athists and in 2000 Bashar al-Assad.

So, while we may feel sadness over the loss of this historical vacation destination, the very ruins we long to visit are themselves evidence of the empires — including our own — who have fought and are continuing to fight for domination.

Where we are, there is war. But clearly this applies unequally across the globe. It might be truer to say that where we want to be, there is war. Huge efficiencies are in store for whichever prince or empire is able to subdue the peoples along this seam. Huge costs and losses of efficiency will follow from losing this war.

So, what about the alternative strategy? We could, after all, invest equivalent amounts of capital — indeed, probably substantially less — educating, training, housing, clothing, and caring for the communities along this seam, preparing them for self-government and independence. But, the consequence of this strategy would be very nearly the reverse of the current strategy. Gone the efficiencies from cheap labour and rent. Gone the terror and fear that drives young men and women to work for private military subcontractors. And gone the dream of pliant and well-behaved client states whose lands and people supply the efficiencies upon which our relative peace and leisure are based.

But, think this through. The efficiencies produced by cheap labour and land (rent) are nowhere near as productive as the efficiencies produced by education, security, the rule of law, civil liberties, and freedom. In the long run, we would be much better to redistribute the efficiencies we have pillaged from these regions back to the communities from which we stole them in the first place. Ah, you say, but there’s the rub. Redistribution of these efficiencies would entail a regulation regime fundamentally different from the current one, which rewards the wealth of the leisured class for its skill in appropriating the efficiencies of everyone else. And this means that the very last thing that this leisured class wants is an educated, skilled, safe, secure, and self-governing population along this seam.

What are they fighting for? For whom are they fighting? Against whom? The answers have never seemed clearer.