One of my favorite all time movies is Monty Python’s “Life of Brian.” And one of my favorite scenes from that movie comes towards the end, when a chorus of victims hung on crosses by Rome’s occupying forces in Palestine break out into song: “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.”

This scene from “Life of Brian” was brought to my mind when I began reading Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of our Nature: Why Violence has Declined. Just as there are many reasons irrespective of the evidence why individuals might hold that violence is declining, so there are many reasons why individuals might cling to the notion that violence is on the increase. Every four years in the United States the party out of power seeks to show that there has been a rise in violence during the tenure of the party in power, while the party in power seeks to show that violence has declined under their leadership. Yet, since the causes for violence — largely social and economic insecurity — are not so easily mitigated during a party’s term in office, such claims on both sides are needless to say completely meaningless. Nevertheless, as this week’s Republican convention illustrates, since politicians are pitching their rhetoric to voters whose only sources of information are sources interested in political outcomes, there is good reason to feel that, as another blogger noted earlier this week, we have entered a post-truth economy.

So, too, there are the perennial nay-sayers, pre-millennial Evangelicals, who are doctrinally committed to superimposing texts describing the destruction of the Temple in C.E. 70 and other apocalyptic events onto the current “end times.” The social, political, and economic climate of the world must get ever worse before the Messiah returns a second time to rid the earth of all God’s enemies; which is to say all of those identified in the Republican party platform. Or, on the other side, we have doctrinally disturbed Marxist-Leninists who also hold to a kind of Messianism: social, political, and economic circumstances will grow progressively worse until the global south and the militant north join hands, sing one round of “Kumbaya” or the “Internationale” (take your pick) before ridding the earth of the “running dog capitalist pigs” and their “lackeys.” And don’t forget the sophistication points we earn when we take dim views of the future.

The problem, however, is really one of framing. Are we talking about homicides, which form the central frame in Pinker’s book? Yes, without question, as state carceral institutions have grown more powerful and sophisticated, but also as states have developed more sophisticated means to defuse and deflect both legitimate and illegitimate rage, homicide rates decline. Moreover, if we look at political communities that divert a significant portion of their wealth to improvements in health, education, and welfare, homicide rates virtually disappear. Or, are we talking about state-sanctioned mass violence? In this case, we can restrict our frame to the last century, a century that includes the two largest state-sanctioned die-offs in history, World Wars I and II. We can then look at the last three quarters of a century and conclude, correctly, that state-sanctioned violence has declined. Although all of us have reason to feel that this decline is good news, we should not allow this good news to overshadow potential costs entailed by the reining in of state-sanctioned mass death. For example, to what extent can we ascribe this decline to the elimination of resistance to globalization, the eradication of whole civilizational forms whose members, for a variety of reasons, may not have been inclined to embrace the new world order? In what ways, therefore, might the decline in officially sanctioned mass death point to forms of discipline and domination that fail to meet the rigorous criteria we have set for what does and does not constitute “violence”?

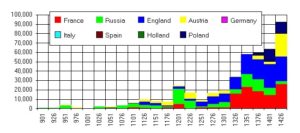

But what happens when we broaden our frame to cover not the past century or so, but to include all of human history? Nor does this question arise, as some may suspect, from a purely theoretical interest in the macabre. For over a decade now I have been splashing the below image onto the screens of lecture halls:

For me it highlights an easily overlooked dimension of late medieval-early modern history. The crusades, which we often portray as excessively brutal and violent, make but scant appearance. Rather is it the conflict among Europe’s powers that exact the highest price. Why should this be?

To explain this dramatic rise in officially sanctioned mass death, we need to bear in mind that even these numbers are mercifully low when set in the context of the centuries that were to follow: the violent eradication of communities in the Americas beginning in the late 15th and then filling the 16th centuries, wars of succession and the religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries, the revolutions and imperial violence of the 18th century, the European wars of the 19th century, but then the excessively violent 20th century. To be sure, since 1944, states have generally been satisfied to engage in low-level, although fairly constant, conflict that flies just under the radar. But, my point is that the continuous expansion of state sanctioned mass violence against which we are comparing this brief lull actually took off in the fourteenth century. Why?

Here, briefly, is the story my students have heard. For nearly all but the last .1 per cent of their 2.4M year history, human beings have clustered in smallish nomadic groups. Then, sometime between 6,000 and 4,000 years ago, at a number of points around the globe, roughly simultaneously, individual families located near arable land or rich supplies of fish and game, proved able to impound the labor of other families. To this impounded labor we owe the great architectural, artistic, and literary monuments of civilization, produced to satisfy the passions and egos of the families that ended up on top, built upon the efficiencies generated by families on the bottom.

But there is another story here that we rarely hear, told by those who neither built nor enjoyed the monuments to civilization. Because up until the dawn of the modern era, most families on the face of the globe did not labor on behalf of overlords. Most families escaped into the hills, into the deserts, onto the islands, or escaped to colder climates, with rockier soils, precisely to avoid having their labor impounded by the tyrants in the riverine valleys, the deltas, or rich, fertile coastal regions. We do not hear their stories because, having not appropriated the efficiencies produced by others, these communities proved unable to erect the dazzling monuments or pen the great works of literature we associate with civilization. Nevertheless, evidence of their presence never lies too far outside the story-line followed by more civilized authors. In the Bhagavad Gita, the Epic of Gilgamesh, and the Hebrew sacred text can be found clearly visible traces of their presence, in stories that usually cast these mountain, island, desert or forest people in the role of divine emissaries sent to warn the riverine or coastal peoples of divine wrath on account of their unholy practices and unjust ways.

For most of human history, the vast majority of human beings preferred such communities to the impoundment of their labor, goods, sons and daughters. They would rather flee that serve the interests of a royal family. And, so, while we focus our attention on these big families who left big footprints in history — we know their monuments, we know of their epic wars and conquests — the vast majority of human beings slipped away unnoticed under the radar. They also slipped away, however, because among such small, thinly scattered, nomadic communities, there is a distinct comparative advantage to flight over fight. Since the fowl and fauna are plentiful and the watering holes are well-known, the costs of fighting over this or that plot of soil far outweigh the benefits from simply fleeing to the next watering hole, the next mountain, the next desert oasis, the next island. Indeed, the fact that we know so little about these nomadic communities, even though they made up the vast majority of people on the planet, is ample evidence that they left virtually no footprint, their temporary homes quickly swallowed up under fresh vegetation, awaiting exploitation by the next wanderers who happened upon them.

Viewed with this wide lens, the period often under scrutiny, from 4,000 B.C.E. to the present, or more often 1700 to the present — scrutiny that often leaves entirely unexamined the mountain, desert, forest, and island peoples — we cannot help but end up with a very distorted picture indeed. This picture, viewed entirely from the vantage point of the state, shows how the state has gradually mastered tools of coercion and cajoling, laws and institutions, that have reduced our violence against one another (homicide), and, at least since 1944, violence between states (war). What these figures overlook is the dramatic spike in violence that accompanied the rise of the modern nation-state in the early modern period.

Let us assume that innovation and economic expansion are possible only through the accumulation and concentration of efficiencies. Under this assumption, it would surely be highly unusual for us to observe the kind of unprecedented innovation and economic expansion that we do in fact find beginning in the 14th century absent a concurrent accumulation and concentration of efficiencies. This concurrent accumulation and concentration of efficiencies is what we call capitalism, which emerged in 14th century Europe when the abstract time marched out on mechanical clocks (a Chinese innovation) was used not to measure intervals between prayer (its original application) but to measure the working day. This in itself was of course an efficiency-generating innovation since it enabled entrepreneurs to bypass messy negotiations with clergy, nobility, and trades over “just price” and “just wages.” Liberated from the distortions introduced by these negotiations, entrepreneurs could measure, precisely, how much time it took to make any good and then derive both wages and prices from this time given specific sets of market conditions. The first such illustration, in fact, that we have of clocks being used in this way is in Ghent in 1324.

But let us also assume that harnessing the efficiencies generated by labor in this way beginning in the 14th century required more than a revolution in time, as David Landes calls it. It required a top to bottom revision in an entire range of social, political, and economic regulations, all of which had originally been designed under the assumption that all of the major interest groups of the day — clergy, nobility, burgers, and tradesmen — would play an active, deliberate role shaping prices and wages and conditions at the local market. To give just one example, it had been the clergy’s traditional role to protect the welfare of baptized Christians — to, in effect, represent God’s interest for the poor, the worker, the widow, and the orphan — at the negotiating table. Similarly, trades organizations were advocates for their members, ensuring that tradesmen from other markets, where goods might be manufactured more cheaply, were either kept out or had to pay a high price to enter. The nobility, obviously, had an interest in general social welfare: keeping the peace. And all of these factors came under consideration when negotiating just wages and prices for any municipality. Now enters the entrepreneur who with unerring accuracy can pin-point the amount of time it takes and number of men or women it takes to bring any good to market. In the face of such indisputable evidence, who needs input from clergy or nobility or trades organizations?

Consider for a moment, however, the costs of realizing these new efficiencies. When just wages and prices were explicitly negotiated, prices reflected the “externalities” (economists would say) of poverty, effective demand, and social and political peace. When wages and prices are determined by abstract time, these externalities must be accounted for elsewhere. Karl Polanyi and EP Thompson have documented how, in order to enforce a new set of laws and regulations to ensure free markets, states also had to create a number of institutions to handle the exploding costs arising from externalities — from recently impoverished farmers pushed off traditional lands because those lands could now generate more money through grazing than farming; or from the explosion of “vagrants” and “vagabonds,” wanderers (from vagrer, “to wander”) into the countryside and city by new economies unleashed by market forces; or from the exploding industry of property disputes that required an expansion of courts and administrative offices.

And, yet, far more important from our vantage point is the carceral system required to bring a population that had been accustomed to the messy and inefficient procedures of purely local negotiations into line with market forces. Markets, after all, run most efficiently in the absence of distortions. Purely local laws and customs, therefore, almost by definition, introduce distortions into markets. There is thus an inherent violence or coercive necessity implied wherever communities are brought into markets. This was surely the case when European powers fanned out across the globe pulling one after another community into their markets and, in the process, laying waste to thousands of years of accumulated custom and tradition which they judged — correctly — to be inefficient. But before they could ever impose the rule of law and markets on communities elsewhere in the world, these European powers first had to impose them on their own subject peoples, their own citizens, in the expansion of a carceral system that aimed at eliminating purely local customs and traditions and at bending all communities to the single market system of the nation-state. Look wherever you will, this is the story of the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. This accounts for the historically unprecedented spike in state sanctioned mass violence observed across the face of the globe.

So, what possibly could Steven Pinker be thinking? His book says it all. Yes, with the growth of this extensive, all-encompassing carceral state, homicides have declined. And, yes, viewed in the very, very short run, restricting our window to the modern epoch, we could say that even state sanctioned mass death has decreased over the past seventy years. But one senses that Mr Pinker wants to say more than this. He wants to say that the human race has become more enlightened, that we are more evolved, and that this has taken place because we have a clearer vision of how we are all connected to one another and our fates and fortunes are all intertwined as one.

One way to think about this holistic vision is metaphysically. If there is such a thing as a world spirit pulling all of the universe forwards, and if consciousness is an extra-human quality of which human beings have themselves only recently become aware or sufficiently aware, then the global proliferation of meditation circles, retreats, spas, health clubs, all connected to one another virtually on the World Wide Web is evidence enough that all of us are operating on a higher plane.

But another way to think about this vision non metaphysically is to recognize how the elimination of purely local, individual laws, customs, languages, traditions, religions, and spiritual practices and the spread of global laws, institutions, regulations and markets has brought us all closer together into a single, integrated, comprehensive, universal system of knowledge and truth: the modern, capitalist world system.

Is it too much of a stretch to call this comprehensive integrated system the current iteration of capitalism? And is it any wonder that it has appeared at the same moment that a holistic vision has arisen to comprehend its spiritual significance?

For Mr Pinker as for many others I think the significance of the virtuous trajectory is that it offers a quasi-scientific, non-theistic, but nevertheless spiritually rich way to talk about hope. Two problems: (1) I find it problematic that this trajectory coincides so perfectly with the appearance and expansion of global capitalism; and (2) I find it convenient that this perspective ignores 99 per cent of global history in order to make its case. A much stronger case, I believe could be developed were we willing to cast a critical eye on the crucial developments that unfolded in 14th century Europe, developments that eventually led to the complete destruction of nearly all of the cultural forms that until then had graced our planet. Yet, since this casts a critical eye both on the present and the future, my guess is that this approach will not be embraced as warmly as the story about our “better angels.”

So, with Monty Python, repeat after me: “Always look on the bright side of life.”