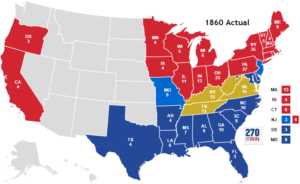

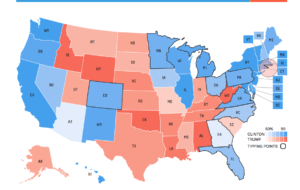

As astonishing as it may seem, where voters stood on slavery and states rights in 1860 is a fairly good gauge of where they will stand today on Trump v Clinton, which may help to explain why Donald Trump has fallen into fourth place (behind Clinton, Stein, and Johnson) among African American voters. But that is not my point.

My point is that the culture of slavery is alive and well south of the Mason-Dixon. Why? Ideally, when the delegates to the Constitutional Convention discussed republican institutions, they aimed at the Athenian ideal of a free, educated, wealthy and leisured public servants. Of course, ideally Aristotle had excluded both farmers and businessmen from those qualified for public service, since both in his view were dependent on labor for their livelihood, thus creating the moral hazard that they might use public office to promote private self-interest. With these two critical exceptions, southern plantation owners and northern businessmen recognized in themselves the qualifications for public service.

But this left the critical point of representation. Who would public servants represent? Again, ideally, they would represent citizens. Yet, who are citizens? And, again, Aristotle was the authority. Citizens were those who, like those who represented them, were healthy, wealthy, and wise. Upon this criteria, however, plantation owners recognized that they were at a disadvantage. For although their populations were roughly equal, there were far more individuals in the north who qualified for citizenship. It was to remedy this advantage that northerners agreed to allow southerners to count each slave 3/5ths toward representation.

Two points: private property herein gained representation in an institution for which res publica, the wealth we hold in common, was to have been the guiding principle. Indeed, 1787 is a watershed precisely for this reason: southern delegates were permitted to turn republican ideals on their head, elevating private property to the guiding principle of their national form. The second point, however, is that this property came specifically in the form of labor. This meant that when labor organized collectively in the northern states for bargaining power, workers in the south, for whom labor-cum-private-property had become a guiding national principle, could not easily organize without at the same time disavowing their “nation.” These two related points were central to the 1860 election. And they remain so today.

The third point that needs mentioning is how these two points are related to the right to bear arms, which, for southerners has since the seventeenth century, always meant both the right to prevent anyone from seizing my private property — my wealth, my slaves — and the right to suppress rebellion by my slaves, who are my property. Guns have always been directed against the central authorities, who may try to seize my property, and, defensively, against that property itself, my slaves. In other words, it has never been about a well-trained militia.

Of course, what this also means is that southerners have never fully bought into republican values and institutions, standing ever ready to renounce republicanism and set out on their own. Remember, until Nixon’s “southern strategy,” the south was solidly democratic; philosophically, it still is. It is the north, and the democratic party, that now best represent republican values and principles.

Take another look at the two maps above. That solid red in the north on the 1860 electoral college map? That is the republican vote. The blue in the south? That’s democratic.