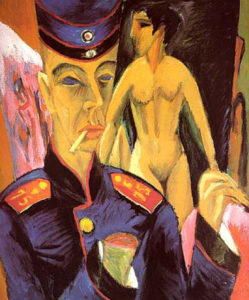

As we careen toward the end of the semester, students have grown anxious, not only because of outstanding papers and final examinations, but also because the future seems so unpromising. As a white European American male, I have tried to recognize the security built-in to my identity. This security has brought me to reflect critically on other moments of precarity, the Weimar in Germany, Periclean Athens. Is it unhealthy to notice and even to be drawn to these epochs? Of all the periods of classical writing and art, none parallels the fifth and fourth centuries BCE in Greece. Was there any period in German art and writing more prolific than the 1920s and 1930s?

Is it pornographic to contemplate these stories and forms, born out of extreme anguish, turbulence, war, and pain; to find them attractive?

Only two generations ago, it was settled that democracy and free markets would stretch far into our future, disappearing well beyond the visible horizon. Works such as Carl Schmitt’s Concept of the Political, written in 1928, republished in 1932, seemed novelties, theoretically interesting but practically useless. My students read Concept of the Political this semester as though it were a contemporary work, written this morning about our world. When they then read John Maynard Keynes’ “The World’s Economic Outlook,” written in 1938 for Atlantic, they could not help but gasp:

In the past, therefore, we have not infrequently had to wait for a war to terminate a major depression. I hope that in the future we shall not adhere to this purist financial attitude, and that we shall be ready to spend on the enterprises of peace what the financial maxims of the past would only allow us to spend on the devastations of war.

For then we remember that, yes, our post-war prosperity and the unflinching commitment of Europeans to social democracy were both predicated upon a world war that left millions dead and that destroyed the fixed capital of a whole continent. Was this the price we paid for Buddenbrooks or Das Boot? Prior to war social inequality and social immobility were both far greater in Europe than in the US. War is a great leveler, performing far more efficiently that which we only reluctantly, if at all, perform during times of peace. Aristophanes wrote during a war-induced plague.

In ten, twenty, or thirty years, stories will be written about us, about our resistance. Our paintings will be displayed, or books republished. Documentaries will be broadcast about our shielding of Muslims, Mexicans, and foreigners from the free-for-all pogroms authorized by our highest political leaders. Our literature will be celebrated.

Am I arguing against resistance? No. I am simply registering what resistance looks like. I am registering a painting, a poem, a photograph. I am registering universities closed down and shuttered, dormitories entered seizing the undocumenteds known to reside there. I am registering professors relieved of their posts. I am registering paintings removed from galleries, replaced with “more suitable” works.

“We have all been here before.” So intoned poets when the US was attempting to eliminate democracy in southeast Asia. Walter Benjamin invoked a similar mood, when, contemplating the fascist uprising in his own Germany, he paused to honor the hopes of the dead:

The past carries with it a temporal index by which it is referred to redemption. There is a secret agreement between past generations and the present one. Our coming was expected on earth. Like every generation that preceded us, we have been endowed with a weak Messianic power, a power to which the past has a claim. That claim cannot be settled cheaply. Historical materialists are aware of that.

I include “historical materialists are aware of that” because to eliminate it would cheapen the prophecy. The current “spiritual” generation, not unlike the “spiritual” generation in Germany, has no need or desire to “connect the dots” since they enjoy direct, immediate access to the divine. The “weak Messianic power,” by contrast, is dependent upon the connects, not vertical, but horizontal — horizontal and, so, dubious, questionable, flawed, and so “weak.”

Can we prevent the fire-storm building on the horizon, on the frontier between Russia and Europe, extending deep into the subcontinent, and encircling the Mediterranean? Can we prevent Marine Le Pen from prevailing in France or the succession of Angela Merkel in Germany? No. We cannot.

Am I wrong to imagine the symphonies that will be composed, the poems that will be written? They are already ringing in my ears. The photographs, not yet processed, are already on the wall of my skull.

But none of this can deter us from shielding those who are most vulnerable. Our cities, our universities, our homes must become refuge — welcoming places, full of fruit, honey, fat, wine — for those who would be victims. And when we open our cities, universities, and homes in this way, we make ourselves not only safe harbors, but targets. We cannot do otherwise. The laws passed in Washington, DC; the warrants issued; the officials dispatched. They simply cannot concern us. We must stand firm.

And, then, as enemies of the state, we will be punished and some, perhaps many, will pay the ultimate price. “We have all been here before.”

But, I was actually thinking about the art, the music, the literature, the dance — the amazing work that emerge during such times as we now are passing through. Is it pornographic to anticipate, to desire, such works, such times?