In the Episcopal cycle of readings (if you are not celebrating William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, 1645) today we find the story of Cain and Abel, and Abel’s murder of Cain:

And Adam knew Eve his wife; and she conceived, and bare Cain, and said, I have gotten a man from the LORD. And she again bare his brother Abel. And Abel was a keeper of sheep, but Cain was a tiller of the ground. And in process of time it came to pass, that Cain brought of the fruit of the ground an offering unto the LORD. And Abel, he also brought of the firstlings of his flock and of the fat thereof. And the LORD had respect unto Abel and to his offering: But unto Cain and to his offering he had not respect. And Cain was very wroth, and his countenance fell. And the LORD said unto Cain, Why art thou wroth? and why is thy countenance fallen? If thou doest well, shalt thou not be accepted? and if thou doest not well, sin lieth at the door. And unto thee shall be his desire, and thou shalt rule over him. And Cain talked with Abel his brother: and it came to pass, when they were in the field, that Cain rose up against Abel his brother, and slew him. And the LORD said unto Cain, Where is Abel thy brother? And he said, I know not: Am I my brother’s keeper? And he said, What hast thou done? the voice of thy brother’s blood crieth unto me from the ground. And now art thou cursed from the earth, which hath opened her mouth to receive thy brother’s blood from thy hand; When thou tillest the ground, it shall not henceforth yield unto thee her strength; a fugitive and a vagabond shalt thou be in the earth. And Cain said unto the LORD, My punishment is greater than I can bear. Behold, thou hast driven me out this day from the face of the earth; and from thy face shall I be hid; and I shall be a fugitive and a vagabond in the earth; and it shall come to pass, that every one that findeth me shall slay me. And the LORD said unto him, Therefore whosoever slayeth Cain, vengeance shall be taken on him sevenfold. And the LORD set a mark upon Cain, lest any finding him should kill him. And Cain went out from the presence of the LORD, and dwelt in the land of Nod, on the east of Eden (Genesis 4:1-16).

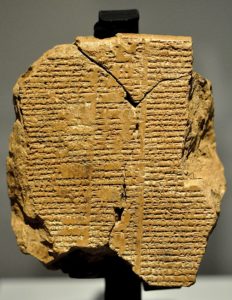

As well it should, the story evokes different interpretations for different communities. No doubt, for rabid meat-eaters, it provides a warning against vegetarians and vegetarianism. (You know that they are trying to seduce your children; right?) For me, however, the Cain and Abel story sends me rushing to my bookshelf for my Penguin edition of the Epic of Gilgamesh.

The story intrigues me not because of its flood story, which bears such a striking resemblance to the flood story told in Genesis, but because of what these ancient stories tell us about settled and wandering communities. Nearly without exception, Yahweh is unhappy with settled, agricultural, communities. Like the wild man Enkidu, Yahweh prefers the wanderers.

The story intrigues me not because of its flood story, which bears such a striking resemblance to the flood story told in Genesis, but because of what these ancient stories tell us about settled and wandering communities. Nearly without exception, Yahweh is unhappy with settled, agricultural, communities. Like the wild man Enkidu, Yahweh prefers the wanderers.

It might seem as though this preference for wanderers arises because of the long sojourn of God’s people in their journey to the promised land. “You shall answer and say before the LORD your God, ‘My father was a wandering Aramean, and he went down to Egypt and sojourned there, few in number; but there he became a great, mighty and populous nation'” (Deuteronomy 26:5); echoed in Hebrews 11:38: “They were stoned, they were sawed in two, they were put to death by the sword. They went around in sheepskins and goatskins, destitute, oppressed, and mistreated. The world was not worthy of them. They wandered in deserts and mountains, and hid in caves and holes in the ground.”

When she created Enkidu, God also made him a wanderer:

The goddess Aruru, she washed her hands,

took a pinch of clay, threw it down in the wild.

In the wild she created Enkidu, the hero,

offspring of silence, knit strong by Ninurta.

All his body is matted with hair,

he bears long tresses like those of a woman:

the hair of his head grows thickly as barley,

he knows not a people, nor even a country.

Coated in hair like the god of the animals,

with the gazelles he grazes on grasses,

joining the throng with the game at the water-hole,

his heart delighting with the beasts in the water.

A hunter, a trapper-man,

did come upon him by the water-hole.

One day, a second and then a third,

he came upon him by the water-hole.

When the hunter saw him, his expression froze,

but he with his herds – he went back to his lair.

Epic of Gilgamesh (Tablet 1, 100-112)

The tyrant and misogynist Gilgamesh, by contrast, is representative of the settled agricultural community.

On the surface, the story tells how the wild man Enkidu is tamed and civilized. In fact, however, it tells how Enkidu tames Gilgamesh. For when Enkidu learns that the tyrant Gilgamesh exercises the so-called droit du seigneur — the right to have sex with soon-to-be wed brides in his realm — it is Enkidu that intervenes on behalf of the people:

Enkidu with his foot blocked the door of the wedding house,

not allowing Gilgamesh to enter.

They seized each other at the door of the wedding house,

in the street they joined combat, in the Square of the Land.

Tablet 2, 110-114

Moreover, it is Enkidu who takes Gilgamesh on a journey, wandering through the wild forests and lands; not subduing or conquering these lands, but learning from them and learning how to live as a wanderer in mutual interdependence on the land.

Back to Cain and Abel. Why did God prefer Abel’s offering over Cain’s? A common diaspora reading of the story finds in God’s preference for Abel evidence of God’s rejection of “works righteousness”; where Cain must plant, water, and cultivate his offering, Abel finds it whole, present, ready to kill and offer without any works. Like the sacrificial animal God provides to Abraham — by faith — in place of Isaac, Abel’s animal offering illustrates faith.

By faith Abel offered to God a better sacrifice than Cain, through which he obtained the testimony that he was righteous, God testifying about his gifts, and through faith, though he is dead, he still speaks. . . . By faith Abraham, when he was tested, offered up Isaac on the altar. He who had received the promises was ready to offer his one and only son, even though God had said to him, “Through Isaac your offspring will be reckoned.” Abraham reasoned that God could raise the dead, and in a sense, he did receive Isaac back from death. (Hebrews 11:4, 17-19).

This common diaspora interpretation of the Cain and Abel story is liable to overlook the underlying theme: wandering in search of a better country.

All these people died in faith, without having received the things they were promised. However, they saw them and welcomed them from afar. And they acknowledged that they were strangers and exiles on the earth. Those who say such things show that they are seeking a country of their own. If they had been thinking of the country they had left, they would have had opportunity to return. Instead, they were longing for a better country, a heavenly one (Hebrews 11:13-16).

We display a neolithic prejudice in our interpretations of ancient stories. I would argue, however, that, like the Epic of Gilgamesh, they instead invite us to admire and emulate our paleolithic forebears: like Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; and, evidently, like Abel. But why this divine preference for our paleolithic forebears?

If we take King David as a type, he is not altogether different from the emperor Gilgamesh. He takes what he wants. He entertains no debate from his subjects. He rapes whomever he wishes. He commands them to erect monuments, royal palaces, and (as an afterthought) a temple for Yahweh. To which God replies:

Go and tell my servant David, ‘This is what the Lord says: Are you the one to build me a house to dwell in? I have not dwelt in a house from the day I brought the Israelites up out of Egypt to this day. I have been moving from place to place with a tent as my dwelling. Wherever I have moved with all the Israelites, did I ever say to any of their rulers whom I commanded to shepherd my people Israel, “Why have you not built me a house of cedar?”’ (2 Samuel 7:5-7).

David, who, in a challenge from Saul savagely kills and strips the foreskins from two hundred Philistines as trophies. The emperor Gilgamesh has nothing over on King David when it comes to naked brutality.

Leaving us to wonder: what is actually entailed in the neolithic revolution? What is required to settle an area, to plant it, water it, cultivate it, harvest it?

Our neolithic prejudice has it that the wanderers, like Enkidu, are the dangerous, uncivilized, uncultivated ones; that David and Gilgamesh are to be emulated. Yet, that is not at all the story told, either in the Epic of Gilgamesh or, for that matter, in Second Samuel. Indeed, I would argue that all of these ancient stories are seeded with an underlying hostility to the settled, neolithic agricultural communities, precisely on account of the cost entailed securing and maintaining these communities. For 2.5M years, human beings were migratory; only during the last 0.01M years have humans settled in permanent communities and only in the last 0.001M years has urban life become dominant. “My father was a wandering Aramean” could be the core text in Deuteronomy. But might it also supply the interpretive key to the Cain and Abel story?

Settled agriculture communities appear only where a single family proves itself powerful and violent enough to requisition the labor and daughters of the other families with which it is wandering. This is the testimony not simply of Hebrew sacred text, but sacred texts across the globe. The vast majority of families escape into the hills, into the deserts, across the seas, into the icy, inhospitable tundras. In these places, they are safe from the tyrannical domination of the settled, neolithic communities whose kings, princes, and emperors wish only to requisition their labor and care for themselves.

Enkidu, the savage, will have nothing of it. He stands in the doorway to prevent Gilgamesh from raping the betrothed.

As I reread the Cain and Abel story this morning, I am reading it through a lens carved in ancient Mesopotamia, where, as everywhere in the ancient near east, settled communities were at odds with the wandering tribes. Abel, the wanderer, the hunter, the backwoodsman, brings his sacrifice, an animal, that Yahweh finds more acceptable not because God is a carnivore, but because God, too, is suspicious of the settled agricultural communities, represented by Cain’s agricultural offering. God, too, is wandering, seeking a “better country, a heavenly one.”