Tomorrow bright and early I will be heading off to San Francisco State University to participate in a discussion of how and why we need to be resisting the neoliberal university.

I hope you will be able to join me or one of the other panels that will be held throughout the day.

My take — perhaps a minority among tomorrow’s presenters — is that the neoliberal university is normal for capitalist societies. Survey higher education before 1940 if you don’t believe me. Its almost uniformly white, wealthy and male. The real anomaly in higher education for capitalism falls between 1940 and 1980, when working families and traditionally underserved families began to ship their sons and their daughters off to universities in historically unprecedented numbers; in such large numbers that their very presence began to reshape higher education in fundamental ways.

It was not simply that the educational goods market expanded. It expanded in ways that reflected its new clientele. To the traditional disciplines were added interdisciplinary studies and area studies, which, I Wallerstein’s claims notwithstanding, were not simply a response to State Department needs, but to the growing diversity of the liberal university. African and African American Studies, Latin American Studies, Gender Studies, Women’s Studies, and Queer Studies were only peripherally related to State Department interests. And, yet, they unquestionably reflected the changing demographic of the liberal university.

But, if we delve into the reasons for this shift, many of us may be disappointed. We would like to believe that we were simply growing more progressive, more liberal, more open, more accepting; which we were, but not simply.

In 1938, the US Congress began its unprecedented spending spree. By 1945 it will have allocated close to $4.2 trillion to defeat nationalism in Asia and fascism in Europe. That’s not counting the Marshall funds, which added another $14 billion to the national budget. The point is, much of this money wound up in the bank accounts of working families, including working families of color, which suddenly found it within their means to send their children off to university — a fact not lost on admissions officers. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s universities competed for this marginal dollar suddenly appearing in the bank accounts of working families. With Japan’s and Germany’s industrial sectors in ruins, these working families, nearly fifty per cent of whom enjoyed good union jobs, ruled the roost. So long as the US industrial sector was expanding, so too would the fortunes of working families; and with them the universities to which they were sending their children.

As the consumer base of the university changed, so too did the product they were offering.

The problem is: we never abandoned a university firmly grounded in private capital markets. Least of all did we abandon this university in the 1960s and 1970s, which progressives and leftists almost universally embrace as the paradigm for the diversifying, progressive, liberal institution of higher learning. To cast this university — our university — as a consumer-driven institution seems cruel and unnecessary. But it is absolutely necessary to cast it in this way. Otherwise we will not fully appreciate the steep terrain before us.

When Germany and Japan reentered the game in 1968, their productivity began placing competitive downward pressure on prices and so investor returns. To his credit, President Nixon attempted to implement (1) universal single-payer healthcare; (2) free higher education; and (3) high speed and light rail, in an attempt to restore US competitiveness. All three were shot down by a Democratic-controlled Congress. As a last resort, Nixon took the dollar off the Gold Standard and let it float on global currency markets.

A weak currency hurts creditors and (temporarily) helps debtors. Consumers in the educational goods market barely noticed a change. Tuitions increased, but so too did wages. What did not change was productivity. Or, rather, productivity declined. Nixon’s fix was just that and nothing more. It led to a decade of “stagflation.”

The present educational goods market was created in 1979 when Fed Chair Paul Volcker increased interest rates by nearly 20 per cent. Suddenly the debts accumulated in the 1970s grew prohibitively expensive. Businesses stopped borrowing money. Huge lay-offs followed. The vastly strengthened dollar helped creditors and (permanently) hurt debtors. It is therefore from 1980 forward that we date ballooning student debt, increasing tuition, and administrators preoccupied with efficiency and productivity.

And so the neoliberal university — which is to say, the old pre-1938 university — blossomed, again.

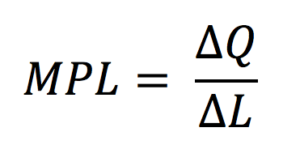

In economic language, administrators and investors became preoccupied with:

where the Marginal Product of Labor equals the change in the quantity of some good (or, rather, its value) over the change in the labor required (or the value of the labor required) to produce that quantity.

Here, education is reduced to its marginal value to investors and consumers.

But there is an alternative. If we take Q to be not a good’s monetary value or even the quantity of that good, but take it instead to be its quality, we can then ask whether we are sufficiently educating our public (given any specific quality and quantity of instruction). If our aim is a sufficiently educated public, then the marginal efficiency of instruction is achieved where and only where Q is satisfied: only where sufficient educational outcomes are achieved. Q is not a monetary amount. Nor is it a quantum of students paying tuition. It is actually an educational outcome. Short of this outcome, we are not investing enough in education.

(Obviously the same holds true for other values: health, leisure, housing, whose value is not measured in monetary units, but rather in desired outcomes.)

As we negotiate our contracts, we need to remember that we are the last defense of superior educational outcomes, as distinguished from marginal profits. We need to this point home. We will not sacrifice our students or their learning. Nor will we sacrifice the learning of communities the university feels compelled to exclude. We are not seeking greater efficiency or productivity or marginal returns. We are seeking superior educational outcomes.