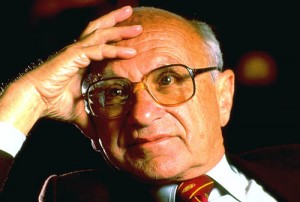

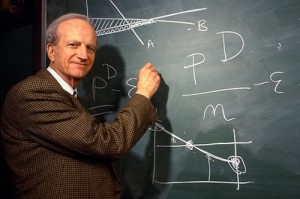

When Gary Becker (1955) and Milton Friedman (1946) joined the University of Chicago faculty, their brand of economic theory was nowhere on the academic map. It is not that economists rejected their brand of economic theory outright; microeconomic theory had its place, guiding the decisions of small businesses and municipal governments, which, because they do not enjoy the authority to print money, are also limited in their ability to manage macroeconomic shifts in supply, demand, interest rates, currency valuation, and so on. This helps to explain why the real economic rock stars of the 1940s and 1950s on through the 1970s were neo-Keynesians. The other explanation, of course, is that it was widely believed that microeconomic theory had proven a complete failure in addressing the Great Depression; a claim disputed by Chicago School economists from the 1930s forward. Whatever the reasons, by the 1950s neo-Keynesians were on a roll and there was no good reason why the Fords, Chryslers, US Steels, or IBMs were about to shift gears and abandon the economic apparatus that had brought them such prosperity. All that was required was some tinkering here and there — shrink the monetary supply, raise revenues, increase interest rates here, lower taxes there — and all would be well. If small businesses wanted to listen to Mr Becker or Mr Friedman, that was their prerogative.

But, of course, as they essays we will begin with illustrate, Mr Becker and Mr Friedman were not about to limit their message to small businesses and local governments. What they wanted was nothing short of revolution; not the peaceable coexistence of macro- and microeconomics, but the complete eradication of macroeconomics and its replacement with the principles of microeconomics. For by doing so they believed economics would be set back on its feet where private consumers and producers through the laws of supply and demand, produce what consumers want at a cost they can afford and for a price that consumers can afford. Such they felt was the secret behind the wealth of nations. Neo-Keynesianism, by contrast, had handed these decisions over to large institutional actors and, worst of all, over to the government, which, rather than allowing market forces to complete their course, found itself in the business of generating the supply and demand to which private consumers and producers were then made subject. They tail they felt was wagging the dog and not the reverse. When neo-Keynesians pointed to the failure of microeconomics in the lead-up to the Great Depression, Chicago School economists pointed to the irresponsible monetary policy of the 1920s that led to the overvaluation of the dollar and of private assets. All of this could and should have been prevented had the Federal Reserve maintained a responsible laissez-faire posture.

But, of course, as they essays we will begin with illustrate, Mr Becker and Mr Friedman were not about to limit their message to small businesses and local governments. What they wanted was nothing short of revolution; not the peaceable coexistence of macro- and microeconomics, but the complete eradication of macroeconomics and its replacement with the principles of microeconomics. For by doing so they believed economics would be set back on its feet where private consumers and producers through the laws of supply and demand, produce what consumers want at a cost they can afford and for a price that consumers can afford. Such they felt was the secret behind the wealth of nations. Neo-Keynesianism, by contrast, had handed these decisions over to large institutional actors and, worst of all, over to the government, which, rather than allowing market forces to complete their course, found itself in the business of generating the supply and demand to which private consumers and producers were then made subject. They tail they felt was wagging the dog and not the reverse. When neo-Keynesians pointed to the failure of microeconomics in the lead-up to the Great Depression, Chicago School economists pointed to the irresponsible monetary policy of the 1920s that led to the overvaluation of the dollar and of private assets. All of this could and should have been prevented had the Federal Reserve maintained a responsible laissez-faire posture.

This coming fall, when I teach my Econ 105 course in the Economics Department at UC Berkeley, I will begin the course by having students read 500 pages of Carl Menger and Alfred Marshall, who, with Leon Walrus, are counted the progenitors of neoclassical economics. Unfortunately (or fortunately, depending on your view point), we will not be reading these authorities this spring. But we should, because what they have to tell us is important for how we read Mr Becker and Mr Friedman. What they tell us is that there is no corner of practical life, no matter how small, that does not play a role in the modern, thoroughly integrated, comprehensive market place. Individual economic actors may feel they play a role — and, in aggregate, in the long run, they do — but in the day-to-day workings of the market, your decisions and my decisions have little or no significance. Put positively, did your or my decisions make a difference, modern neoclassical models, which rely upon large numbers, would not work. One telling fact among many may help us to appreciate the importance of neoclassical economic theory

.

Alfred Marshall was neither a liberal nor a conservative. He really did not care which party was in power. What mattered to him was whether an economist, armed with the knowledge of how any given policy might shape the marginal utility of any given commodity, would have the competence to advise his client — private or public — on the best decision to make, pragmatically, under the circumstances. But he was also able to work from the opposite end of the policy chain. What policies would yield the best outcomes for any given client. For this reason alone, Marshall found it relatively easy to recommend policies that rested all across the ideological map. (For reasons that should be evident, Mr Menger was more ideologically “bent.” Situated in Austria-Hungary, where private and public economic actors engaged in much more deliberate, open cooperation over policy, Mr Menger became a cheer-leader for private economic decision making over public.)

Already by the 1930s, when Frank Knight and Jacob Viner occupied the chairs that Mr Becker and Mr Friedman would inherit, awareness of history at the Chicago School had grown unacceptably thin. Nevertheless, could still produce a series of historical essays, which, although flawed, displayed a grasp of historical awareness completely lacking in their 1950s and 1960s successors. For example, Mr Knight and Mr Viner acknowledged but were also completely comfortable with the anti-democratic and anti-republican implications of free market capitalism. By the 1950s and 1960s, Mr Becker and Mr Friedman were so oblivious to the historical and political implications of their theories that they had no problem peddling their doctrines of private tyranny in the guise of public freedom. Mr Friedman was, in fact, so completely unaware as to ascribe to the framers of the US Constitution anti-federalist doctrines in fact embraced by their opponents, anti-federalists.

But by the 1950s and 1960s it hardly mattered. As we learned from G Arrighi, the third global hegemony had already reached its pinnacle and would soon be entering its financialization stage. And it is here that the “Chicago Boys” showed their true value. As the bottom dropped out of commodity production, Mr Becker and Mr Friedman were poised to argue that this decline in rates of profit were due to government regulation, taxation, and public spending. All that was needed in order to restore value was to privatize and deregulate. Here, too, is where Tito’s 1970s policies come into play. As J Lowinger’s study shows, it was under this conceit that Tito and his successors pursued the path of privatization and deregulation that would eventually give rise to the labor unrest of the 1980s, unrest that in the 1990s blossomed into genocide.

Yet, here in these offerings from Mr Becker and Mr Friedman, written in the 1950s and 1960s, we can already appreciate how their policies are explicitly both anti-democratic and anti-republican. We can already see where neoliberalism is going. We can already feel Srebrenica.