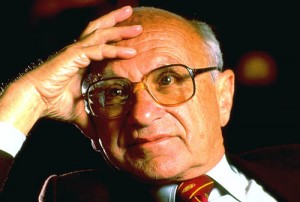

Last Monday we had the privilege of exploring the world of Gary Becker, one of the most mathematically skilled economists of the past century. This week we have the privilege of exploring his charming side-kick, the Boy Wonder, Milton Friedman. Milton Friedman was a good mathematician. But his real skill lay in setting out in a simplistic manner, for mathematical economists who really couldn’t have cared less, why the havoc they were wrecking across the globe was actually righteous.

Last Monday we had the privilege of exploring the world of Gary Becker, one of the most mathematically skilled economists of the past century. This week we have the privilege of exploring his charming side-kick, the Boy Wonder, Milton Friedman. Milton Friedman was a good mathematician. But his real skill lay in setting out in a simplistic manner, for mathematical economists who really couldn’t have cared less, why the havoc they were wrecking across the globe was actually righteous.

Yes, simplistic; because it relied upon the conviction — which turned out to be true — that everyone or nearly everyone who registered for Professor Friedman’s famous graduate course 301 or who read the Readers Digest version was already convinced that what Milty was telling them was true. Price is the leading mechanism in all human transactions and self-regulating free markets are the best mechanisms for determining price; end of story. But that is not why they registered for 301. They registered for 301 in order to master the math that lay behind this metaphysical conviction.

The central piece of math revolves around the beauty of mathematical zero, the empty or null set. Any movement one way or the other away from zero signals a distortion. Now, of course, Alfred Marshall, whose inaugural Principles appeared in 1871, also embraced this central piece of math. An increase in transportation costs or an increase in taxes or an increase in the costs of any factor of production pushes the price that a producer can accept for a product to the right and so naturally introduces downward pressure on the volume of sales — the number of customers prepared to part with the marginally greater amount of capital for the same product or service, all other things being equal. But whereas A Marshall rolled with these shifts at the margins, identifying the ever new equalibria established whenever any factor changed, Milton Friedman, rather magically, embraced the minimizing of economic distortions to zero as the Holy Grail of economic science. Followed to its natural conclusion, this would make a world rid of human history, culture, individuality, and choice the optimal world because in it all things would actually be caeteris paribus; all things would be equal.

Last week we saw how Gary Becker equated the mathematical median with the “rational.” We will see this week how it is around this median also that “freedom” is arrayed. Freedom can be plotted around the median, however, only because and to the extent that producers may rely upon the predictability of this median holding true. I am for a price above or below the median in light of the choices buyers have made and are likely to make in the future. In von Hayek’s phrase, I plan for freedom; I do not plan for planning. When, however, some external agent introduces a factor that does not reflect consumer choice (freedom) — such as a higher tax — the increased cost of my item does not reflect either the buyers’ or the sellers’ decisions surrounding my particular product, but rather a macroeconomic shift that neither of us bargained for. The elimination of such macroeconomically induced shifts becomes the necessary ingredient for extending freedom as far as possible — making the communication between the buyer and seller the point where price is sovereignly determined.

What about monopolies? Friedman will admit that while private monopolies do tend to push prices upward, the monopolist is not free to push the price so far that the buyer cannot afford the item. Moreover, the rational monopolist must still determine where along the supply and demand lines, volume and price maximize profits. In other words, according to Friedman, even the private monopolist, because she or he is interested in maximizing return on investment, will be pushed by the principle of freedom to drop the price or increase the volume in order to maximize returns on investment. Not so a public monopoly, where maximization of utility is subordinated to some extrinsic, non-market, value — such as health or education. But, so devoted is Professor Friedman to his metaphysical center, that he will not even abandon it when it proves inadequate. Thus he can show that when good health is a sufficient public good, self-regulating market forces will drive down costs while at the same time enhancing product quality. If people are still unhealthy, it is (a) because there is insufficient demand for public health; and (b) because public health care programs have so distorted markets as to increase the value of poor health. In an undistorted, self-regulating free market, all of those who wanted health care would have health care at a cost they could afford and a quality for which they would be willing to pay.

Zero. The median. The elimination of market distortions. What does freedom look like? This is what freedom looks like. The absence of constraint. Freedom reduced to the freedom of Kant’s Transcendental Subject. Freedom, which by definition has no body and therefore offers no resistance, no drag, pushing the supply and demand curves only where they would naturally fall.

Of course, as we will see, history itself offers one of the most noxious and troublesome distortions for Friedman’s metaphysics. The radical republicanism of the framers of the US Constitution or the French Revolution? Deeply troubling. They are troubling because instead of granting the free market self-regulating powers, republican values invite the public to identify the wealth they hold in common and the ends to which they will put that wealth. Res publica, the Latin phrase translated everywhere into Republic (or its cognates) is in the US more faithfully translated simply Commonwealth, therein preserving the original sense of shared, public wealth. And, yet, so committed is Friedman to his Transcendental Subject and to its sovereignty that through sheer force of will and declaration eliminates republicanism from the historical record, proclaiming the framers nothing but advocates, like himself, of self-regulating free markets.

And, where the US Constitution or its amendments do seem to tip toward a role for the public, Friedman recommends that we simply amend the Constitution to replace the public with the private marketplace. Why? Because of zero. Because people, the public, by definition, constitute a drag on the economy; a distortion.

The numbers do not lie.