While vacationing in Southern California this week, I happened upon a visible and tragic symbol of all that is wrong about the United States today, a Barnes & Noble bookstore. This tragedy is epitomized by one book, Ann Coulter’s latest rant against all things liberal: Demonic: How the Liberal Mob is Endangering America.

Like Barnes & Noble, there is enough truth in Coulter’s diatribe to pique her readers’ interest. But, like Barnes & Noble, the overall effect is, well, demonic.

Like the Straussians from whom she failed to learn, Coulter traces all that is noxious about the “liberal mob” to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose rejection of reason and satisfaction with bodily satisfaction inspired revolutionary Jacobins to stir up the uneducated mob for short term political gains. Yet, as I wander through the local B&N, past shelves of Rick Perry’s Fed Up!, Mitt Romney’s No Apology, Ron Paul’s Liberty Defined, Bill O’Reilly’s Killing Lincoln, and piles and stacks of other demagogic tirades, I am taken back to Plato’s Gorgias, which lays bare Pericles’ archetypal rise to power on the shoulders of Athens’ poorly educated and poorly compensated masses. Here, as Leo Strauss himself pointed out, is the archetypal “liberal” mob.

But then Coulter reproduces the same error of which Strauss was guilty. In the face of the “liberal” mob, she retreats to Plato and to his Republic. Remember, it was Pericles’ courts, stocked with poorly educated and undercompensated stooges hand-picked by Pericles himself, that tried and condemned the good man Socrates. And, of all Plato’s dialogues, Gorgias best captures Plato’s initial reaction to this injustice.

Gorgias is a rhetorician, a speech writer, a PR man, who boasts to Socrates that he can teach anyone how to convince anyone else that he or she is right.

SOCRATES: You said just now that even on matters of health the orator will be more convincing than the doctor.

GORGIAS: Before a mass audience – yes, I did.

SOCRATES: A mass audience means an ignorant audience, doesn’t it? He won’t be more convincing than the doctor before experts, I presume.

GORGIAS: True.

SOCRATES: Now, if he is more convincing than the doctor then does he turn out to be more convincing than the expert?

GORGIAS: Naturally.

SOCRATES: Not being a doctor, of course?

GORGIAS: Of course.

SOCRATES: And the non-doctor, presumably, is ignorant of what the doctor knows?

GORGIAS: Obviously.

SOCRATES: So when the orator is more convincing than the doctor, what happens is that an ignorant person is more convincing than the expert before an equally ignorant audience. Is this what happens?

Years later, a more mature and circumspect Plato addresses this problem in his Republic. Knowing that it is impossible to solve the problem of the ignorance of the crowd, Plato instead develops his system of guardians, good men who are also sufficiently wise to recognize the futility of “casting pearls before swine.” And so they are compelled, for the sake of the higher good, to lie to and secretly deceive the ignorant masses.

This is the solution settled upon by Strauss and embraced by every want-to-be self-styled guardian, such as Coulter, ever since. And, so the stacks and piles of misdiagnoses and bogus snake-oil therapies that litter the shelves of the local B&N. None of these snake handlers are doctors. None of their therapies actually cure.

Do they turn out to be more convincing than real doctors? Sure they do, at least before a mass audience. “So when the orator is more convincing than the doctor, what happens is that an ignorant person is more convincing than the expert before an equally ignorant audience.” Indeed.

There was, however, another answer that Plato overlooked: to avail all Athenians of an education and to provide them with material means sufficient to distinguish between Gorgias’ fine art and true knowledge. Plato despaired of this alternative because he knew that he could not convince Athens’ elites to part with either their wealth or their power in sufficient quantities to actually elevate Athenians to the level of truly informed citizens.

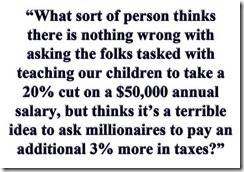

And this is the irony—entirely missed, of course, by Ann, Mitt, Ron, Bill, and all the rest of these want-to-be self-styled guardians. Coulter and the others direct their venom precisely against those who understand and are trying to realize this alternative: high quality public education and sufficient wealth and leisure to become responsible, engaged citizens. Instead, she and her colleagues are exemplars of Gorgias’ fine art, mere rhetoricians, or, as Plato called them, panderers, appealing, like Pericles, to the ignorant masses in order to advance their own private ends and the ends of their wealthy, powerful, and satisfied friends.

As you well know, Ann, this is the real mob. They are the mob because you and your friends want them to be a mob. And, rather than push for universal, high quality, public education, or a more equitable tax policy, you and your fellow Gorgiases instead want to make sure that this mob will ever remain a mob.

And, I see that B&N is only too ready to help you. Shame.