There is so much that is good about Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything that we may be inclined to ignore or completely overlook those inconsistencies in her analysis that tend to weaken her (and our) movement. Two inconsistencies in particular stand out: the first comes to light in Ms Klein’s repeated references to “the West” and “Western Culture”; the second appears in her critique of “extractivism” and her failure to grasp the historical and social specificity of extraction. In both of these instances, Ms Klein builds her case on popular, though deeply flawed and superficial, interpretations of what has happened to the world over the past four hundred years. This superficial reading weakens her (our our) movement because it fails to accurately identify the mechanisms driving climate change, diverts our attention elsewhere, and so promotes battles where there need be none while overlooking the sites of contestation that are desperate for our attention.

The story about “the West” and “Western Culture” adopted by Ms Klein is itself one of the leading narratives of the culture she is anxious to critique. In its modest version, based loosely on a popularized version of Max Nordau’s turn-of-the-last century Degeneration (itself a popularization of ideas circulating in Europe since the Enlightenment), humankind got off track when we sought to ground our existence empirically, scientifically; when we reduced ourselves to machines, mere bundles of atoms and molecules; when we reduced our minds to Cartesian calculators; when we reduced the world around us to mere cause and effect. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was among the early prophets to call attention to this degeneration when he noted how civilization and rationality were hostile to the very instincts, feelings, and connections to nature plowed under in the march of civilization. In its more robust version, popularized first by Friedrich Nietzsche and Max Weber, but then by a host of others — Martin Heidegger, Theodore Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Hannah Arendt, Allan Bloom — the perversion evident in contemporary culture goes all the way back to the dawn of time, when Apollonians, those who think, differentiated themselves from Dionysians, those who feel, and when this differentiation was legitimated and codified among the Athenian Socratics. Within this grand narrative, “the West” and “Western Culture” entail the universalization and globalization of this perversion. Two groups only escape contamination: those at the top, the superior men and women, who act out of themselves, “authentically” as Martin Heidegger has put it, without needing extrinsic, external, authority or law, and those “natural” peoples who escape from civilization and from its enslavement. To be non-Western or to escape from Western Culture means at the very least to reject every “rationalism,” every “scientism,” every “reductionist” or “linear” approach to the world and to embrace the “irrational,” the “sensuous,” the “natural” and “decentred,” “spiritual” character of all reality.

The story about “the West” and “Western Culture” adopted by Ms Klein is itself one of the leading narratives of the culture she is anxious to critique. In its modest version, based loosely on a popularized version of Max Nordau’s turn-of-the-last century Degeneration (itself a popularization of ideas circulating in Europe since the Enlightenment), humankind got off track when we sought to ground our existence empirically, scientifically; when we reduced ourselves to machines, mere bundles of atoms and molecules; when we reduced our minds to Cartesian calculators; when we reduced the world around us to mere cause and effect. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was among the early prophets to call attention to this degeneration when he noted how civilization and rationality were hostile to the very instincts, feelings, and connections to nature plowed under in the march of civilization. In its more robust version, popularized first by Friedrich Nietzsche and Max Weber, but then by a host of others — Martin Heidegger, Theodore Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Hannah Arendt, Allan Bloom — the perversion evident in contemporary culture goes all the way back to the dawn of time, when Apollonians, those who think, differentiated themselves from Dionysians, those who feel, and when this differentiation was legitimated and codified among the Athenian Socratics. Within this grand narrative, “the West” and “Western Culture” entail the universalization and globalization of this perversion. Two groups only escape contamination: those at the top, the superior men and women, who act out of themselves, “authentically” as Martin Heidegger has put it, without needing extrinsic, external, authority or law, and those “natural” peoples who escape from civilization and from its enslavement. To be non-Western or to escape from Western Culture means at the very least to reject every “rationalism,” every “scientism,” every “reductionist” or “linear” approach to the world and to embrace the “irrational,” the “sensuous,” the “natural” and “decentred,” “spiritual” character of all reality.

Ms Klein pays homage to this narrative throughout her text. Two sites in particular deserve attention. In the first, Ms Klein pays homage to the second, more robust narrative, here citing Thomas Sancton’s 1989 Time magazine article covering Time’s naming of the Earth “Planet of the Year.”

In many pagan societies, the earth was seen as a mother, a fertile giver of life. Nature — the soil, forest, sea — was endowed with divinity, and mortals were subordinate to it. The Judeo-Christian tradition introduced a radically different concept. The earth was the creation of a monotheistic God, who, after shaping it, ordered its inhabitants, in the words of Genesis: “Be fruitful and multiply, and replenish the earth and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the fowl of the air and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.” The idea of dominion could be interpreted as an invitation to use nature as a convenience (74; citing Santon, Time, 1-2-1989).

Anyone with even a passing familiarity with the composition of Hebrew sacred text — and I assume this includes Ms Klein — knows, first, that there are few foundational stories embedded in these texts that were not first circulated under different cover throughout the fertile crescent, most notably in the Epic of Gilgamesh, where, as in the Hebrew sacred text, one of the leading themes concerns the conflict between mountain/wilderness communities and urban communities. Second, however, even in the Hebrew sacred text itself, we find a notable tension between those narratives that favor migratory, unsettled, non-urban social forms and those narratives that favor permanent, settled, urban, and predictably hierarchical social forms. Finally, nothing could be more obvious to anyone studying long-term climate change how little sense it makes to ascribe practices that emerged in the late Roman period (i.e., already in the Common Era) to beliefs circulating in the sixth and seventh millennias B.C.E., inviting readers to exhibit just a bit of curiosity over precisely how the first audiences of these babylonian narratives might have originally understood them.

This highlights where Ms Klein is at her weakest, where she seeks to grasp the mechanisms driving climate change. In place of mechanisms, Ms Klein often falls back on pop-psychology and sociology, mistaking individuals within a particular class strata or cultural formation for the mechanism otherwise missing from her interpretive framework. This, in turn, brings her to overlook emancipatory tendencies prematurely excluded by her interpretive categories. Thus, for example, no one anywhere in the world, least of all in “the West” itself, would have recognized western Europe as anything more than the coldest, most sparsely populated, most inhospitable, most backward, most fragmented, and least administratively developed region of the globe prior to the 14th century. Outside of a few pockets of urban settlement, most “Europeans” lived sustainably in small, isolated, semi-migratory communities. Members of these communities were extraordinarily skilled at reading the signs of the world around them — migratory patterns, meteorological patterns, the canopy of the heavens, seasonal shifts, shifts in fern and fauna upon which they depended for their very existence. And, yet, Ms Klein appears to feel that these sensibilities somehow skirted “the West.”

This is a crisis that is, by its nature, slow moving and intensely place based. In its early stages, and in between the wrenching disasters, climate is about an early blooming of a particular flower, an unusually thin layer of ice on a lake, the late arrival of a migratory bird — noticing these small changes requires the kind of communion that comes from knowing a place deeply, not just as scenery but also as sustenance, and when local knowledge is passed on with a sense of sacred trust from one generation to the next. How many of us still live like that? Similarly, climate change is also about the inescapable impact of the actions of past generations not just on the present, but on generations in the future. These time frames are a language that has become foreign to a great many of us. Indeed Western culture has worked very hard to erase Indigenous cosmologies that call on the past and the future to interrogate present-day actions, with long-dead ancestors always present, alongside the generations to come (158-159).

When she fixes upon “the West” as a locus of climate-changing ontology, Ms Klein therein no doubt plays to a theme deeply engrained in left-wing and progressive lore, but a theme that completely fails to meet the truth test among trained anthropologists, historians, and social scientists. It simply didn’t happen the way that Ms Klein suggests.

Another way to get at this same theme is to ask why it was in “the West” that the extractivist economy became socially generalized? And one way to answer this question is to take careful note of the notoriously fragmented, decentred, and “backward” character of western Europe prior to the 13th century and then to ask how did it all come together? The answer is not only intriguing, but actually better fits Ms Klein’s emancipatory intentions. When, in the 13th century, cloistered communities were seeking more accurate ways to measure the intervals between times of prayer (since there was a global cooling at the dawn of the new millennium), they hit upon the Chinese escapement mechanism as the perfect solution. The escapement mechanism introduced intervals of abstract, absolutely equal time units to be measured, ringing a small bell that awakened “Frere Jacques” who then awakened the other brothers with a larger bell. The only problem was that the brothers were not the only ones so awakened. Awakened also were country and towns folk scattered in the vicinity of the monastery, folk accustomed to the variable, diurnal rhythms marched out by the seasons. Now they were awakened at all hours of the night. However, it did not take long for entrepreneurs, eager to escape the regulatory restrictions placed on them by crown, cloth, and trades, tested the novelty of regulating the work day in accordance with the rhythms of the monastic bells. As David Landes has noted, this marked the first time, anywhere, that the value of productive human action was measured not by complex political and social negotiations, but by the equal units of abstract time hammered out on mechanical clocks. In another couple centuries, western Europeans were growing increasingly accustomed to differentiating abstract value from the material substances in which this value was felt to be contained, and to differentiating as well a material world lacking in essential value from the immaterial value given to that world by labour. From that point on, Europeans began to shift their focus away from the production of material goods and toward the production of abstract value; that is, they produced material goods in order to produce immaterial value, and not the reverse. Thus was capitalism born, not out of a Protestant Ethic as Max Weber had mistakenly claimed, but out of a transformation in practices and social sensibilities which, in turn, gave rise in the sixteenth century to Protestantism.

Capitalism was the first and only coherent, integrated, rational institutional and legal form known to western Europe, which, owing to its initial fragmentation proved particularly susceptible to capitalism’s unique calibration of time, labour, and value.

This also offers a more satisfying explanation for the “extractivism” featured throughout Ms Klein’s account. Yes, civilizations extract wealth — in India, in Mesoamerica, in China, in central Africa, in Rome; that is what civilizations do. But since they aim at material wealth and not abstract value, they quickly run up against material barriers. Where capitalism differs from run-of-the-mill historical extractivism is that, since its aim is abstract value and not material wealth, it is continuously driven to consume and eliminate the material world with ever greater efficiency in order to generate ever higher returns on abstract value. But this also highlights a more compelling reason why, at least where their “productivist” goals were concerned, the Soviet bloc and the capitalist West were a lot closer to one another than many might think. Perhaps following Ferdinand Braudel, Karl Polanyi, and Giovani Arrighi, Ms Klein would like to find this similarity in institutional centralization: “Authoritarian socialism and capitalism share strong tendencies toward centralizing (one in the hands of the state, the other in the hands of corporations)” (178). She also faults both for their expansionist productivist outlooks: “both keep their respective systems going through ruthless expansion — whether through production for production’s sake, in the case of Soviet-era socialism, or consumption for consumption’s sake, in the case of consumer capitalism.”

Again, however, Ms Klein fails to identify the mechanism driving this expansionist extractivism, allowing ideology to fill in the gaps left by weak social and historical analysis. However, a more rigorous approach would actually reinforce Ms Klein’s position. Since both capitalism and Soviet style communism equate value with abstract labour time expended neither is equipped to recognize when and where a material limit has been reached. This also offers a better explanation for why redistribution of wealth, while important, fails to adequately address the question central to climate change, the limits to production and consumption which figure so prominently in Ms Klein’s story. Only as we sever the social, political, institutional and regulatory relationship between abstract value and abstract labour, only as we begin to recover other ways of valuing human action and goods, only then will the limits imposed by what, after all, is a material world begin to reassert themselves.

This mechanism is but poorly captured in terms such as “centralization” or “extractivism” which serve as cognitive, mental snap-shots where what we need are deep causal linkages capturing the social and cultural mechanisms driving human action. It is this, unfortunately, that is lacking in Ms Klein’s otherwise quite informative and important account.

“Make them citizens and have them vote”? Not in your life. And, so, what happened instead was that southerners accepted federalism in exchange for slavery.

“Make them citizens and have them vote”? Not in your life. And, so, what happened instead was that southerners accepted federalism in exchange for slavery.

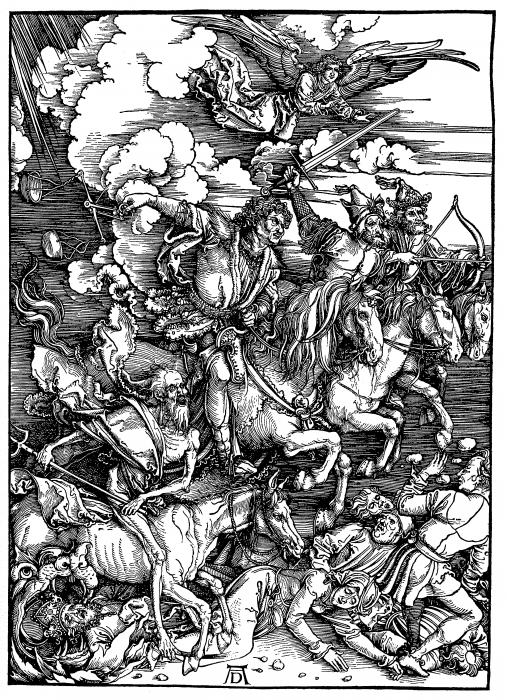

And then, of course, there is the natural assumption that we will find what is revealed attractive and welcoming. Were the four horsemen of Albrecht Dürer’s Apocalypse attractive? Were they welcoming? And what about the disclosure announced by their appearance?

And then, of course, there is the natural assumption that we will find what is revealed attractive and welcoming. Were the four horsemen of Albrecht Dürer’s Apocalypse attractive? Were they welcoming? And what about the disclosure announced by their appearance?