Joseph W.H. Lough

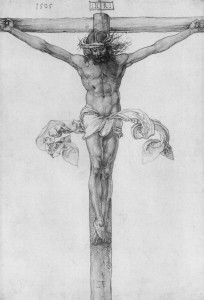

The body is at the center of Easter. Easter is about the body.

As part of my Lenten practice this season, I have taken up the Marin Bible Challenge, a set of daily readings that promises at its conclusion to guide readers through the entire Hebrew and Christian sacred texts. Three weeks ago, while wading through Leviticus – yes, Leviticus! – I experienced an epiphany. Even if you are not too familiar with Leviticus, this may sound odd. Leviticus? Really? Yes, really.

For those of you who don’t have a clue what I am talking about, Leviticus is the third book in the Pentateuch, the five books traditionally ascribed to Moses, wherein we find the details of the Mosaic Law.

4And if the bright spot be white in the skin of his flesh, and the appearance thereof be not deeper than the skin, and the hair thereof be not turned white, then the priest shall shut up him that hath the plague seven days:5and the priest shall look on him the seventh day: and, behold, if in his eyes the plague be at a stay, and the plague be not spread in the skin, then the priest shall shut him up seven days more: 6and the priest shall look on him again the seventh day; and, behold, if the plague be dim, and the plague be not spread in the skin, then the priest shall pronounce him clean: it is a scab: and he shall wash his clothes, and be clean. 7But if the scab spread abroad in the skin, after that he hath showed himself to the priest for his cleansing, he shall show himself to the priest again: 8and the priest shall look; and, behold, if the scab be spread in the skin, then the priest shall pronounce him unclean: it is leprosy.

9When the plague of leprosy is in a man, then he shall be brought unto the priest; 10and the priest shall look; and, behold, if there be a white rising in the skin, and it have turned the hair white, and there be quick raw flesh in the rising, 11it is an old leprosy in the skin of his flesh, and the priest shall pronounce him unclean: he shall not shut him up, for he is unclean. 12And if the leprosy break out abroad in the skin, and the leprosy cover all the skin of him that hath the plague from his head even to his feet, as far as appeareth to the priest; 13then the priest shall look; and, behold, if the leprosy have covered all his flesh, he shall pronounce him clean that hath the plague: it is all turned white: he is clean. 14But whensoever raw flesh appeareth in him, he shall be unclean. 15And the priest shall look on the raw flesh, and pronounce him unclean: the raw flesh is unclean: it is leprosy. 16Or if the raw flesh turn again, and be changed unto white, then he shall come unto the priest;

You get the idea. In short, it prescribes how any faithful Jew should respond to nearly every conceivable situation she or he might encounter. The natural question is “Why?”

At this point, I do not want to haggle over when or how the Hebrew Bible, the Tenach, was composed. Suffice it to say that the kinds of prescriptions set forth, ad nauseum, in Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy were recognized and, where possible, practiced by all who called themselves Jews as early as the fourth century BCE.

My interest in these laws has to do with the body, because Easter is all about the body.

Now for my epiphany. My epiphany was simply this: were it not for the detailed knowledge if not strict observance of the Law, there is no question in anyone’s mind but that the people we call the Jews would, like all of the other Semitic tribes wandering through the Arabian Peninsula, almost surely have been completely assimilated. And they would have been assimilated no matter how unique, detailed, or intricate their theology. The Jews had to engage with their experience of the divine in a bodily form, through practice. For, absent this practice, which entailed the engagement of their bodies and not simply their minds, the Jews would have become simply one more Babylonian sect.

There it is. That is my epiphany.

Now, you are no doubt wondering, what has this to do with Easter?

Contemporary religion and spirituality have no bodies. To be a believer today entails no more than an inward change, a shift in my heart, my disposition. Similarly, I need no body in order to be spiritual. Indeed, having a body may even be a deterrent to true spirituality, for what I really need is to escape the endless cycle of pain, suffering, and becoming and dissolve into the peace where being and non-being meet. I must rid myself of the body-ego, must transcend its limitations. Or, should I desire somewhat more content, I can think or meditate my way into or onto the true path.

This is because, historically, the problem with faith and with religion was that they possessed bodies, and that meant that they had skin, walls, boundaries, limits. It meant that they were formed, shaped, structured, limited, bounded. It meant that they were one thing and not another, they said one thing and not another. Indeed, the problem with religion and spirituality, historically, is that they said anything at all; not only because language is limited, whereas everyone knows that the divine is unlimited, limitless, and beyond all expression, but also because once it achieves expression, the divine becomes subject to all of the limitations and misunderstandings and drawbacks to which all speech is subject.

This also of course holds for all laws, institutions, and procedures. Today therefore we celebrate religions – or, more properly, spiritualities – without walls, without rules, absent all or any institutional forms or fixed rituals or traditions.

So, what should we call this completely disembodied, disembedded form of social subjectivity? Shall we call it emancipation, total emancipation, so total that it includes both body and soul?

Historically I fall within a long line of activists who, ever since the French Enlightenment, have needed and who have even occasionally constructed what could be called a secular liturgy. By secular here, I do not intend anything bad or evil or sinful. By it I only mean a liturgy that is timely, saecularis, of time. And, so, periodically we invent a new timely liturgy. We did so following the French Revolution. We did so following the Russian and the Chinese Revolutions. And some would say that we did so following the American Revolution as well. It might even be said that the Beats constructed something of a secular liturgy.

Such liturgies, however, always suffer from the same deficiency, which may explain their effervescent, brilliant, spectacular, but always fleeting character. In every instance, such liturgies are constructed intentionally according to some sweeping, often quite detailed, intellectual vision of what we need to be and where we need to go: Bob Dylan as high priest, cantor, as liturgist.

What distinguishes the Law of Moses from Bob Dylan’s (or Macklemore’s or K’Naan’s) poetry is that the Law of Moses was not designed as a vehicle for anything. Rather was it a record of practices whose aim, if anything, was to preserve the practical bodily integrity of a particular community in its exile. And for this reason, they could not have been invented or constructed or developed with an aim to do anything else except to confirm and reinforce that identity.

We, by contrast, are not a people, not a movement, not a community; we are not in exile, but to the contrary are completely at home. Or, if we are not at home, if we feel alienated, we are completely at a loss as to what beyond therapy, meditation, and prayer or (quite literally) losing our selves we could possibly do to return home from exile. Because there is no home to which we could return. And, no, the present day Israeli state is no more a home than is present day America.

If we have a body, it is the commodity form and its immaterial value; which is, of course, no body.

But, as I said, the center of Easter is the body.

Walter Benjamin, who perhaps understood this better than anyone else, records the following in his second thesis from the “Concept of History”:

The past carries with it a secret index by which it is referred to redemption. Doesn’t a breath of the air that enervated earlier days caress us as well? In the voices we hear, isn’t there an echo of now silent ones? Don’t the women we court have sisters they no longer recognize? If so, then there is a secret agreement between past generations and the present one. Then our coming was expected on earth. Then like every generation that preceded us, we have been endowed with a weak messianic power, a power on which the past has a claim. Such a claim cannot be settled cheaply. The historical materialist is aware of this.

If the divine has a passable body, if the divine can suffer death and be buried, then and only then can sense be made of our exile or sense be made as well of our possible return. If, on the other hand, the divine is perfectly impassable, if it is not subject to death and to suffering, or if the aim of the divine is to emancipate us from this body of death – a death from which, according to tradition, the divine could not even emancipate itself – or if our present goal is to arrest and transcend the cycle that is so intimately intertwined with our bodies; well, then, of course, no amount of Midrash can possibly save us.

Repetition – telling the story over and over – standing, kneeling, bowing, praying, repeating, remembering, facing this way and not the other, listening, learning, arguing; all of these built, constructed, limited and delimiting bodily postures and expressions are what Easter is all about. It is about the body.

Without them we cannot possibly survive our exile. Without them we cannot possibly hope to return home.