I just now completed an initial reading of Pope Francis’ papal encyclical Laudato Si’. The encyclical seeks to restore the claim on and responsibility for all of creation that, since the 14th century, humanity has been increasingly willing to hand over to market forces. I have some criticisms of the encyclical, in particular Francis’ attempt to imbricate Rome’s peculiar reproductive ethics into care and protection of the environment. In this sense, the encyclical reiterates themes that, since the nineteenth century, have dominated Catholic social teaching: its suspicions of technology in general and, more particularly, of the manipulation of nature. I will return to these themes in a moment.

Broadly speaking, however, Francis brought together several related interpretive frameworks: the biblical recognition of nature as Creation; the biblical emphasis on the social and moral character of knowledge; defense of the poor and, so, the intimate relationships between economic policy, social justice, and Creation; and, ubiquitous throughout, Catholic social teaching, albeit read through, if not an explicitly Heideggerian, then at least an implicitly phenomenological lens.

Although Laudato Si’ is chock full of references both to biblical and to canonical authorities, it is accessible to readers lacking special knowledge either of Christianity or of religion. That is because it is grounded in the deceptively innocuous observation that everything is related. Our actions have consequences. Our convictions drive our actions, so they too have consequences. Our laws and regulations, which are themselves products of our convictions, shape our lives together in ways that have consequences. When we shape the natural world, the natural world, in turn, shapes us. These deceptively innocuous observations lose their banality when reinterpreted theologically, not as statements about how nature works, but as confessions about how God has made Creation work, the responsibility God has given to humanity to care for Creation, and as prayers for how religious practitioners might show forth their adoration for God in how they act towards God’s Creation.

The discreet elements of nature are intimately related to one another. And, since our own survival and well-being rest upon not only the bounty of the Earth, but also upon a bounty that is sustainable, we are obviously interested in how the elements of nature relate to one another. We have an existential stake in how they relate. Yet, when we add language about Creation to this formal recognition, we endow it with a sense of eternal significance. Creation, as Pope Francis noted, is going some place. It has purpose, divine purpose. Its grace extends beyond its function for us now. It has integrity in its own right. But this means that our obligation to Creation extends beyond its mere function for us. Creation is blessed.

This original integrity and beatitude was fragmented when, following creation, human beings elected to isolate their obligations to God, Creation, and to one another. A command from God can be considered independently from any one’s judgment and from what any one takes to be his or her best interest. “Did God say . . .?” is a question that arises from the thought that Creation, God, and humanity might have separate points of view. Originally, however, Creation, God, and humanity enjoyed integrity.

But we must therefore distinguish this original, primal, integrity from the gradual, progressive, social and historical integration to which nineteenth century European thinkers first called our attention. This latter integration can be ascribed to the emergence in the fourteenth century of a new economic form — capitalism — whose tendency was to bring all human action and all thought and nature into relationship with one another in a comprehensive, integrated, universal, and consistent market. Obviously differentiating these two is no easy task. And, indeed, we might want to pause to consider why so many radical religious political figures are so attracted to this alternative, capitalist, not divine form of integration. We might also ask why Protestant social teaching differs so remarkably from its Roman Catholic counterpart.

One fruitful avenue for exploration would note how Protestantism feels no theological obligation to integrate fallen Creation and the “fallen world” with the New Creation. Since Protestant social teaching embraces fragmentation within its initial point of departure — faith from works, spirit from body, Creation from nature — its posture towards Creation has proven much more problematic than the Roman posture. Protestants display much less distress isolating their economic activity or their scientific insights from their spiritual life. For Roman Catholics, by contrast, the integrity of Creation is foundational. And, indeed, this surely explains why Pope Francis went out of his way to differentiate his position from the views articulated by nineteenth century romantics, among whom were not a few Roman Catholics, whose opposition to industrialization and to capitalism was at least in some measure an outgrowth of the spiritual discomfort they experienced over the fragmentation and discord that accompanied the rise of industrial capitalism. Protestants, by contrast, have often faulted Catholic social teaching for what they believe is its implicit “works righteousness.” If God wants to save Creation, let God save Creation. If God wants to help the poor, then let God help the poor. Or, in its extreme form: we help Creation (or the poor) best by trusting that God’s will will be done; we dishonor Creation (and the poor) by believing (mistakenly) that their fate is in our hands.

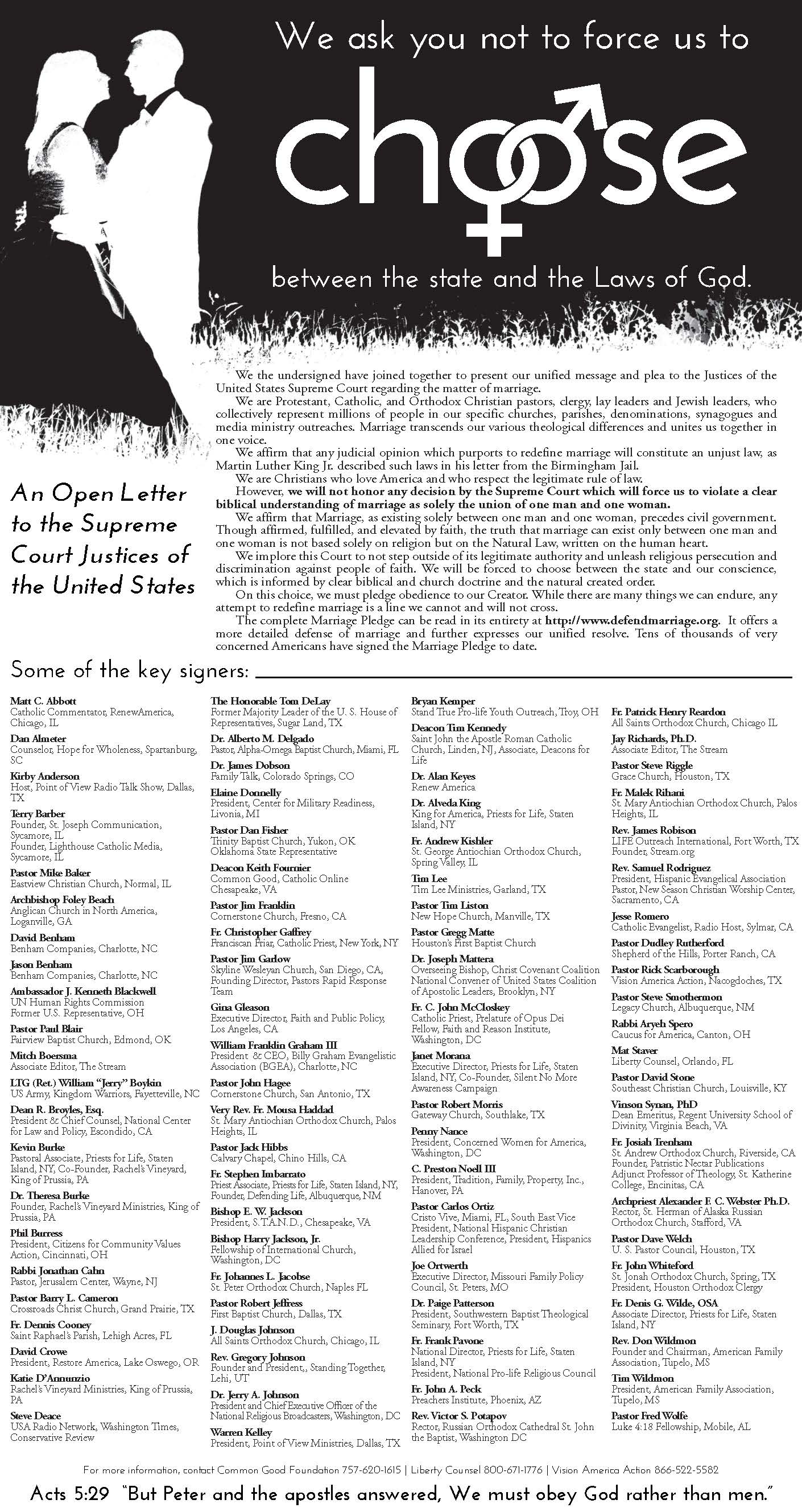

The Roman Church’s emphasis on primal integrity is a powerful tool. Upon it Rome has erected an impressive superstructure of natural theology. It accounts for the Church’s opposition to capital punishment, its opposition to war, to private patents on biological organisms, as well as to the misuse of nature. But, upon it is also based its opposition to abortion rights, its opposition to women’s ordination, and the right of all people to marry. Indeed, as Francis seemed eager to show in his encyclical, you cannot simultaneously laud the Church’s commitment to battling climate change while condemning its defense of the unborn. In Francis’ mind, the two are of a piece. Thus, the encyclical makes clear that the theological foundation for the right to life, including its opposition to capital punishment, its commitment to combatting climate change, its opposition to women’s ordination, and its opposition to capitalism is identical. All appeal to God’s natural order, to Creation.

This may appear to pose a serious dilemma to those of us who are on board combatting climate change and opposing capitalism or capital punishment, but who also embrace women’s choice and women’s ordination. Are we picking and choosing? Are we being inconsistent?

Here, I would advise His Holiness to take a step back and consider an alternative way of inflecting the Church’s teaching. Let us suppose that there was an original integrity to Creation and that that integrity has been violated. And let us further suppose that despoiling Creation bears evidence of the Fall. Everything would then appear to rest on how we differentiate practices, dispositions and forms that were part of the original integrated Creation from practices, dispositions, and forms that arose on account of the Fall. At this point, however, His Holiness would also have to consider what is new about the New Creation that, since Pentecost, has been emerging within the natural, yet fallen, order. Finally, I would invite His Holiness to differentiate the sacred Doctrine of Creation from the everyday first century Stoicism with which it is not infrequently confused. Thus, for example, we have Saint Paul’s defense of Nero on what appear to be stoic grounds in Romans 13:1-7. Paul counts Nero (or Nero’s appointed local rulers) “servants of God” whose laws everyone should obey because, in Paul’s words, no one could rule without God’s will. The Apostle rests his case on the stoic conviction that the whole natural, social, legal and political order form a consistent, interconnected, whole from the very highest cosmic principle to the smallest grain of sand. Both Nero and his court, however, were profligate, immoral, and violent men dedicated, among other things, to temple prostitution, pogroms against Jews and Christians, and who not infrequently engaged in court intrigue involving poison, murder, and sexual impropriety at the highest levels. So, I would invite His Holiness to consider how this stoic principle that the Apostle relies on in Romans 13:1-7 differs, on the one hand, from the original integrity of Creation and, on the other hand, differs from the New Creation that God set in motion on Pentecost.

Are we to judge a woman’s disposition over her own body — which evidently would include not only her right to abort a fetus, but might also involve the dignity of the priesthood or marriage to another woman — a consequence of the Fall? Or might it not be a part of the original integrity of Creation or, perhaps, of the New Creation? For the problem we face here, as His Holiness was careful to emphasize, is that the “social” and the “natural” are not unrelated to one another. Indeed, what we count as “natural” or what we count as part of the “created order” has often been shaped by practices within the societies that define what falls into (or what should be excluded from) these categories. Could it be, then, that we count women’s ordination as “unnatural” only on account of the “science” that defined women in one way and not another? Could it be that we count fetus’ as potential adults because of a “science” that ascribes souls to the unborn (and, even here, not to feminine eggs, but to male sperm)?

Two observations in conclusion. The first observation is that current science does not dispute the role human beings are playing in climate change. Nor as a matter of fact does current science dispute the fact that human sexuality naturally runs a very wide gamut. It always has. One could, it is true, arbitrarily place the freedom of marriage, women’s ordination, and the right to choose under one category or another. But scientifically the fact of climate change falls in the same category as the fact that human sexuality has never been uniformly binary. The Church is on very solid grounds where climate change is concerned. It is on much weaker ground where its sexual and reproductive teachings are concerned.

The second observation is that there is nothing in the Church’s formal distinctions that would prevent His Holiness from counting opposition to women’s ordination or opposition to choice as consequences of the Fall rather than defenses of the the natural created order. Ultimately, that is good news. For it means that, in principle, the Church could maintain the integrity of its principles while shifting its application of those principles. In its application to climate change Pope Francis has written in a manner consistent with these principles. In its application to sexuality, he has not.

anything but good Jewish or Christian rulers. Yet, late medieval and early modern Christian thinkers imagined — as John Calvin imagined — that the authors of Peter’s and Paul’s letters were referring to “Christian magistrates.” Well . . . no. Because in 70, 80, and 90 CE such a thing as a “Christian magistrate” didn’t exist. The pastorals were counseling Christians to obey laws and rulers who were thoroughly secular and pagan — you know, goddess cult stuff, temple prostitution and the like. Indeed, as a kicker, Paul even counsels the Christians in Rome to pay taxes, presumably to support policing the local Jewish population, upkeep and supply of pagan temples, supplying Rome’s soldiers who at the time were engaged in anti-Christian and anti-Jewish campaigns. That, Paul says, is why we pay taxes. “Because of this you also pay taxes, for rulers are servants of God, devoting themselves to this very thing. Render to all what is due them: tax to whom tax is due;custom to whom custom; fear to whom fear; honor to whom honor” (Romans 13.7).

anything but good Jewish or Christian rulers. Yet, late medieval and early modern Christian thinkers imagined — as John Calvin imagined — that the authors of Peter’s and Paul’s letters were referring to “Christian magistrates.” Well . . . no. Because in 70, 80, and 90 CE such a thing as a “Christian magistrate” didn’t exist. The pastorals were counseling Christians to obey laws and rulers who were thoroughly secular and pagan — you know, goddess cult stuff, temple prostitution and the like. Indeed, as a kicker, Paul even counsels the Christians in Rome to pay taxes, presumably to support policing the local Jewish population, upkeep and supply of pagan temples, supplying Rome’s soldiers who at the time were engaged in anti-Christian and anti-Jewish campaigns. That, Paul says, is why we pay taxes. “Because of this you also pay taxes, for rulers are servants of God, devoting themselves to this very thing. Render to all what is due them: tax to whom tax is due;custom to whom custom; fear to whom fear; honor to whom honor” (Romans 13.7).

But Econ 164 will also be unique because instead of reading Marx in the shadow of 1918 (Russia) or 1949 (China), economists are now free to read Marx (as he perhaps always should have been read) in the shadow of 1848-1849. An older generation of Marxists will recall the flurry of excitement surrounding the publication, in English, of Marx’s 1844 Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts. The manuscripts were discovered and first published in the Soviet Union in 1927. They offered a snapshot of a young social theorist still wrestling with a hodgepodge of French socialism, British political economy, and German idealism, a theorist over whose thought the concept of “alienation” hovered imperiously. Not surprisingly, it was with this younger, tormented and troubled, philosophical Marx tucked under their arms that the generation of 1968 engaged authorities not only in Boulder, Austin, Berkeley, Ann Arbor, Madison, and Kent State, but in Prague, Budapest, Mexico, Paris, and Berlin. And it was with this Marx tucked under their arms that our professors, as graduate students, marched into battle to take on “the establishment” only to become disillusioned in the 1970s and then tenured in the 1980s.

But Econ 164 will also be unique because instead of reading Marx in the shadow of 1918 (Russia) or 1949 (China), economists are now free to read Marx (as he perhaps always should have been read) in the shadow of 1848-1849. An older generation of Marxists will recall the flurry of excitement surrounding the publication, in English, of Marx’s 1844 Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts. The manuscripts were discovered and first published in the Soviet Union in 1927. They offered a snapshot of a young social theorist still wrestling with a hodgepodge of French socialism, British political economy, and German idealism, a theorist over whose thought the concept of “alienation” hovered imperiously. Not surprisingly, it was with this younger, tormented and troubled, philosophical Marx tucked under their arms that the generation of 1968 engaged authorities not only in Boulder, Austin, Berkeley, Ann Arbor, Madison, and Kent State, but in Prague, Budapest, Mexico, Paris, and Berlin. And it was with this Marx tucked under their arms that our professors, as graduate students, marched into battle to take on “the establishment” only to become disillusioned in the 1970s and then tenured in the 1980s.