As an economist who holds a Ph.D. in German History from the University of Chicago, I nearly fell over when I read this week’s National Review headline: “Bernie’s strange brew of nationalism and socialism.” Say what? But here’s what author Kevin D. Williamson has to say:

In the Bernieverse, there’s a whole lot of nationalism mixed up in the socialism. He is, in fact, leading a national-socialist movement, which is a queasy and uncomfortable thing to write about a man who is the son of Jewish immigrants from Poland and whose family was murdered in the Holocaust. But there is no other way to characterize his views and his politics (http://www.nationalreview.com/article/421369/bernie-sanders-national-socialism).

What is disturbing about the National Review’s characterization of Sanders is not their discomfort over his economic nationalism, over which I am also none too happy, but their explicit linkage of Sanders with mid-twentieth century German national socialism. For it not only shows a profound misunderstanding of how German national socialism worked and why. It also displays a disturbing misuse of the very propaganda that brought the Nazis to adopt this twisted name. For as anyone who is familiar with German National Socialism knows only too well, while Nazism was surely nationalist, it was in no stretch of the imagination socialist.

What is disturbing about the National Review’s characterization of Sanders is not their discomfort over his economic nationalism, over which I am also none too happy, but their explicit linkage of Sanders with mid-twentieth century German national socialism. For it not only shows a profound misunderstanding of how German national socialism worked and why. It also displays a disturbing misuse of the very propaganda that brought the Nazis to adopt this twisted name. For as anyone who is familiar with German National Socialism knows only too well, while Nazism was surely nationalist, it was in no stretch of the imagination socialist.

This, of course, is an old Hayekian double-switch. The Nazis were socialists. FDR and Clement Attlee (British Prime Minister) implemented socialist-like programs. Germany is a nation. England and the United States are nations.

And there you have it. FDR and Clement Attlee are national socialists. The “road to serfdom” Hayek called it.

Of course, most of Williamson’s article consists of strings of incoherent free association ad hominem.

Bernie’s politics, on the other hand, are the polar opposite of Scandinavian: He’s got a debilitating case of Tea Party envy. He promises not just confrontation but hostile, theatrical confrontation, demonizing not only his actual opponents but his perceived enemies as well, including the Walton family, whose members are not particularly active in politics these days, and some of whom are notably liberal. That doesn’t matter: If they have a great deal of wealth, they are the enemy. (What about Tom Steyer and George Soros? “False equivalency,” Bernie scoffs.) He knows who Them is: The Koch brothers, who make repeated appearances in every speech; scheming swarthy foreigners who are stealing our jobs; bankers, the traditional bogeymen of conspiracy theorists ranging from Father Coughlin and Henry Ford to Louis Farrakhan; Wall Street; etc.

The Scandinavians are socialist; Bernie is socialist; the Tea Party is anti-socialist; the Tea Party attracts large blue collar audiences; Bernie wishes to attract large blue collar audiences; Tea Party speakers are brash; Bernie is brash. Socialists don’t like wealth; the Waltons are wealthy; Bernie doesn’t like the Waltons. Who else criticized the rentier class? Father Coughlin and (Nazi sympathizing) Henry Ford and (antisemite) Louis Farrakhan.

Go ahead, find the argument here. I dare you.

Perhaps Williamson wishes to defend wage and benefit policies that force many of Walmart’s employees on the welfare rolls. Or perhaps he is perfectly OK with the Koch brothers buying elections. Or perhaps Williamson feels that criticizing employers who refuse to pay a living wage or billionaires who buy elections is prima facie evidence of national socialism. Say what?

It is only as you near the end of Williamson’s article that you will read the following admission. “There are many kinds of Us-and-Them politics, and Bernie Sanders, to be sure, is not a national socialist in the mode of Alfred Rosenberg or Julius Streicher. He is a national socialist in the mode of Hugo Chávez.” Well, thanks Kevin for letting us know. Because for several paragraphs it sounded like you were suggesting that Bernie Sanders might be the other kind of national socialist.

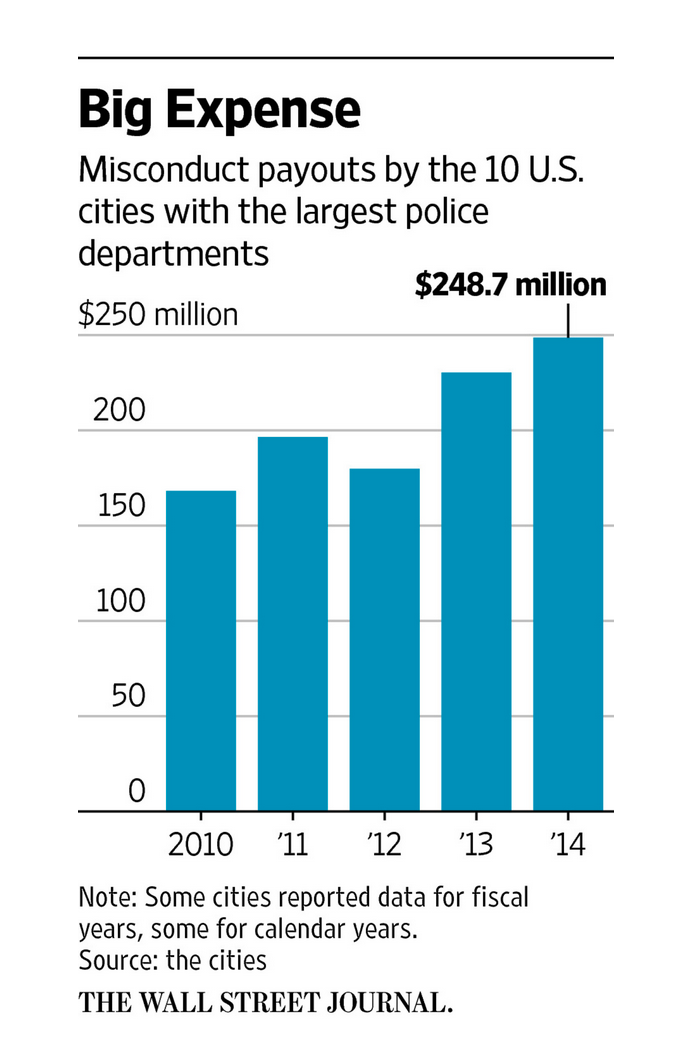

Just to be clear, the German National Socialists were never critical of industries whose owners were opposed to the Social Democrats and left-leaning trade unions. They made league with big German industrialists who, under the Nazis, were permitted to use non-organized Polish, Czech, and Hungarian workers in order to drive down production costs, increase productivity, and pull the German economy out of the Great Depression. Sound familiar?

This is no ad hominem. This is the practice of US industry, much of which depends on undocumented and unorganized labor to keep costs down. But it is not Bernie who is opposed to organized labor or who is urging industrialists to take advantage of the low costs of hiring undocumented aliens. That would be Williamson’s buddies at the National Review. Moreover, it is not Bernie who is behind the well-funded propaganda machine of Fox News and Murdoch a lá Herr Goebbels. Again Williamson has Bernie confused with his friends at Fox News.

This leaves the matter of economic nationalism. Even here, however, Williamson — who evidently has never read a real book about real German economic history — has it upside down. Bernie would love to see Mexico, China, India, and Malaysia pass the same environmental protection and union organizing protections still enjoyed in the United States (no thanks to National Review). All else being equal, Bernie is as big a supporter of free trade as the next guy. But the truth is that industries in Europe and Japan enjoy the luxury of national health care, which relieves them of the cost of providing private health insurance for their employees. And industries in Mexico, China, India and Malaysia don’t suffer under the burden of labor protections that drive up costs or environmental protections that do the same.

All else being equal . . . but it never is. The folks at National Review would be happy if we removed those protections and eliminated the minimum wage entirely. Let workers find their own healthcare. Then America will once again be competitive. Sound familiar? It should. Under the German National Socialists workers lost all of the protections they enjoyed during Weimar. Under the Nazis all worker safety laws were eliminated. When Adolf Hitler wanted a scarce resource, he went and took it by force; you know, kind of Kuwait, Iraq, Afghanistan-like force.

Ad hominem? No. Just the real history of real national socialism in Germany, which bears a far closer resemblance to what the National Review does than to what Bernie advocates. So I have an idea. How about we nominate Kevin Williamson for the new post, the Minister of Propaganda, in a new Republican administration. It is a title and skill set that appears to suit him well.