Stephen Metcalf gets so much right in his long read “Neoliberalism: the idea that swallowed the world” (2017-08-18 The Guardian), that I am tempted to leave well enough alone. The theory supporting neoliberalism can no doubt be described as an idea; and this idea has, as Metcalf argues, had a profound influence on the policies institutions have implemented all around the globe. And he is more than half right to call our attention to the significant role played by Friedrich von Hayek in shaping and then spreading the ideology of neoliberalism, the theoretical scaffolding that supports these policies.

And, yet, repeatedly in his account, Metcalf appears to suggest that it is the idea of neoliberalism — and not the actual practice of capitalism — that has introduced the pain and suffering peculiar to neoliberalism. For those not yet certain they want to wade through Metcalf’s long read, here is my executive summary:

- the utopian ideal of the free market and the dystopian present are causally related; granting the market universal status bears a close relationship to “our current descent into post-truth and illiberalism.”

- von Hayek’s Big Idea — that free markets compose free minds capable of grasping the value of free markets, whereas regulated markets constrain minds in ways that obscure reality — marks a departure Enlightenment wisdom and from classic liberalism, even the classic liberalism of his University of Chicago Colleagues Frank Knight and Jacob Viner.

- When value and price collapse into one another — as they must in von Hayek’s neoliberal ideology — the tautology falsifies any notion of value that might arise outside the sphere of price, i.e., outside the sphere of the market economy.

- By calibrating “liberty” solely to free markets, neoliberal ideology believes that it has shown (a) that free markets alone give rise to objective value; and (b) that values not grounded in market activity are therefore by definition arbitrary and relative

- The authoritarian and illiberal dimensions of post-democratic society arise from admitting only to the singular logic of the free market, all other value formations — democracy, diversity, opportunity, health, art, religion — be damned.

“How can the combination of fragments of knowledge existing in different minds,” [Hayek] wrote, “bring about results which, if they were to be brought about deliberately, would require a knowledge on the part of the directing mind which no single person can possess?”

Metcalf summarizes von Hayek’s Big Idea as follows:

It is a grand epistemological claim – that the market is a way of knowing, one that radically exceeds the capacity of any individual mind. Such a market is less a human contrivance, to be manipulated like any other, than a force to be studied and placated. Economics ceases to be a technique – as Keynes believed it to be – for achieving desirable social ends, such as growth or stable money. The only social end is the maintenance of the market itself. In its omniscience, the market constitutes the only legitimate form of knowledge, next to which all other modes of reflection are partial, in both senses of the word: they comprehend only a fragment of a whole and they plead on behalf of a special interest. . . .

It was Hayek who showed us how to get from the hopeless condition of human partiality to the majestic objectivity of science. Hayek’s Big Idea acts as the missing link between our subjective human nature, and nature itself. In so doing, it puts any value that cannot be expressed as a price – as the verdict of a market – on an equally unsure footing, as nothing more than opinion, preference, folklore or superstition.

But what if the value form of capital behaves more or less just as von Hayek describes it? What if it is not an idea, but the actual composition and expansion of the value form that gives rise to a highly specific way of experiencing the Self, the World, and the Other?

Metcalf would like to situate von Hayek’s Big Idea in the 1930s. Why? Here is my suspicion. Let us suppose that von Hayek’s Big Idea could actually be found much, much earlier: let us say in 1868, 1869, or 1870. And, let us suppose that, Metcalf’s claims to the contrary notwithstanding, the rigorous mathematical modeling to which von Hayek believed the contemporary world could be reduced was already well-developed and fully elaborated by the end of the nineteenth century. Would that make a difference? Noted Cambridge historian Eric J Hobsbawm felt that it would.

Up until the revolutions of 1848 and 1849, European liberals had still felt that economic policies were subordinate to political forces; that, for example, republican institutions and values and democratic process could enjoy precedence over private market forces. The haste and ease with which monarchs and armies dispatched the democratic and republican forces of 1848 and 1849 made it clear to everyone that capitalism would not so easily be made subject to political forces. The political despair that followed from the defeats of 1848 and 1849 generated a full decade of unprecedented economic growth across Europe; almost as though the new economic form fed directly upon political despondency. In fact, the process was somewhat more complex. The same concert of Europe that defeated Napoleon also (and far more easily) dispatched the republican and democratic forces of 1848 and 1849. And it was this concert that also recognized the benefits that could be won from recognizing and empowering private entrepreneurs and investors who, until these revolutions, had largely been locked out of the chief positions in their respective state bureaucracies.

In a microcosm, the U.S. Civil War played out the same dynamic that in 1848 and 1849 had swept across Europe. The technologically superior and far better financed United States devastated the technologically backward, agricultural Confederacy, albeit with not the same ease as monarchs put down the uprisings of 1848 and 1849. Yet, where the economy is concerned, the results were the same. The decade following the end of the Civil War saw unprecedented growth.

More importantly for our purposes, after 1865 the world of capital in general, on both sides of the Atlantic, witnessed an acceleration in the integration of laws, regulations, currency exchanges, information, and trade — all of which worked to create one, singular, integrated, comprehensive economic system. That the expansion of this system had an ideological component is doubtless true. But so too was the actual integration of the system into a complex, dynamic integrated whole.

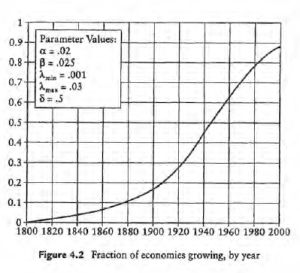

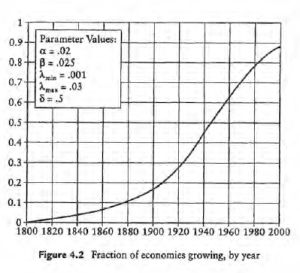

Nobel Prize winner Robert E Lucas, Jr. has represented this integration in the following chart:

Professor Lucas did not fabricate the chart. The data is real. Integration into the global economy gives rise to economic growth. And at present, roughly 98 per cent of the earth is, as Metcalf notes, “swallowed.”

This comprehensive economic integration had an interesting side effect. Beginning in the late 1860s, early 1870s, economists such as William Stanley Jevons, Leon Walras, and Alfred Marshall recognized that a world integrated in this way lent itself to rigorous mathematical modeling. That is to say — the actual economic integration did not follow from but preceded the rigorous mathematical modeling. Here is an example from Jevons’ Theory of Political Economy (1871):

It is clear that Economics, if it is to be a science at all, must be a mathematical science. There exists much prejudice against attempts to introduce the methods and language of mathematics into any branch of the moral sciences. Many persons seem to think that the physical sciences form the proper sphere of mathematical method, and that the moral sciences demand some other method – I know not what. My theory of Economics, however, is purely mathematical in character.

If, however, it was comprehensive economic integration, in fact, not in theory, that invited attempts to grasp that integration in a mathematically rigorous manner, then these attempts are no more ideological than, say, Heisenberg’s theoretical physics. But this means that the question we must ask is how well or poorly von Hayek is able to account for the observed phenomena — and not whether the phenomena, in this case a neoliberal world, exists.

And it is here that von Hayek turns metaphysical, even religious. For, in essence, he ascribes the emergence of liberal institutions to the gradual elimination of economic constraint; when the fact is that economic growth has always, at least since the fourteenth century, been predicated upon massive public intervention into private markets. Prior to the fourteenth century von Hayek’s rational, economizing individual is nowhere in evidence. There is not a shred of evidence indicating that human communities naturally lend themselves to rigorous mathematical modeling.

Since this is so, we need to ask how policies, institutions, laws, and regulations might have given rise to the very real human experience that counts our market dominated world as “natural.” Like his spiritual mentor Carl Menger, von Hayek was a rabid atheist. He and Menger both fashioned themselves men of science and progress. Yet, when they came to reflect on the “economizing individual,” no science — not history, not anthropology, not sociology, not even the far more mathematically rigorous modeling of their Cambridge School enemies — could stand in the way of their deeply religious faith in price as the reflection of basic human liberty. On this one point, von Hayek literally self-lobotomized. Why? What was at stake?

At stake, I would argue, was an entire world. The fact that this world was humanly constructed, fabricated, and terribly recent (no earlier than the fourteenth century) does not detract from its substantial reality. The world von Hayek theorized is our world, the real world: integrated, rational, comprehensive, total, singular. But this is not to say that it is the only possible world. We might imagine, for example, as Metcalf imagines, a world where the interests of families, religious communities, nature, art, and learning collide and collude with one another if not in the absence of private economic forces, at least not under their singular weight of their total domination. We could then imagine a form of freedom different from Immanuel Kant’s “absence of material constrain”; a form of freedom more in line with Nobel prize winning economist Amartya Sen’s “conditions that make for freedom”: education, security, housing, health, food, family, friends — which, as Sen notes, is in line not only with traditional Hindu, Buddhist, and Confucian wisdom, but also with the teaching of “western” paragons such as Aristotle.

But — and this is a huge but — this would mark the end of market capitalism; not markets, but market capitalism. And this von Hayek could not imagine.

After he had recovered from his post-1848 hangover — remember, the Communist Manifesto was published in 1848 — Karl Marx took a long, well-deserved sabbatical in London. At the other end of this sabbatical there emerged a work, Capital, that, rather than faulting the new system for what it was not, instead sought to understand what it was. In a phrase, Marx concluded that capitalism was a comprehensive economic system constructed by the social form: value. He defined value as “a self-moving Substance that is Subject” — that is to say, a rational, goal-directed Agent, or, what GWF Hegel thought of as der Geist or Mind.

A close reading of either von Hayek or K Marx is not possible here. Such a reading, however, would quickly show that von Hayek and Marx were actually quite close in their characterizations of capitalism as universal Mind or Spirit. Where they differed is critical. Where von Hayek felt liberated by this comprehensive, all-encompassing quasi-scientific totality, Marx felt that it was the essence of modern human domination; and where von Hayek believed that this form of domination was hard-wired into human ontology, Marx argued that it was peculiar to a historically specific social form: capitalism.

Metcalf’s description of von Hayek’s Big Idea is terribly good. But what if it is not simply an idea?

The application of Hayek’s Big Idea to every aspect of our lives negates what is most distinctive about us. That is, it assigns what is most human about human beings – our minds and our volition – to algorithms and markets, leaving us to mimic, zombie-like, the shrunken idealisations of economic models. Supersizing Hayek’s idea and radically upgrading the price system into a kind of social omniscience means radically downgrading the importance of our individual capacity to reason – our ability to provide and evaluate justifications for our actions and beliefs.

If von Hayek’s Big Idea is simply an idea, then we can combat it with better ideas — judged better by idea consumers, the public. If, however, von Hayek’s Big Idea is itself an expression of an actual social form — the value form of capital — that it seeks to defend, then the idea, while dangerous, is not the real enemy. Policies that deprive us of art, nature, security, health, learning, and love — these policies themselves bring us to value what remains; and what remains is a cold, uninflected indifference curve indicating with pin-point precision each of our market choices which we then mistake for value and for freedom.