Aristotle, the fourth century BCE philosopher, was familiar with social upheaval. Son of a wealthy Macedonian family, his childhood

Aristotle, the fourth century BCE philosopher, was familiar with social upheaval. Son of a wealthy Macedonian family, his childhood  paralleled that of Phillip of Macedon, the future monarch and eventual conqueror of Athens. During his training at Plato’s Academy in his late teens, Athens, which was almost continuously at war and forced to divert resources and wealth away from more productive uses, continued to convulse under political assassinations and low-level civil war. In 355, weary of the strife on its southern border, Macedon invaded and easily defeated its war-weakened southern enemy. Aristotle returned to Athens with the patronage and protection of his one-time student Alexander the Great, Phillip’s son. He then taught in occupied Athens as an “independent contractor” with the occupying force until Alexander’s death made him the target of anti-Macedonian rebels, from whom he fled, dying a year later.

paralleled that of Phillip of Macedon, the future monarch and eventual conqueror of Athens. During his training at Plato’s Academy in his late teens, Athens, which was almost continuously at war and forced to divert resources and wealth away from more productive uses, continued to convulse under political assassinations and low-level civil war. In 355, weary of the strife on its southern border, Macedon invaded and easily defeated its war-weakened southern enemy. Aristotle returned to Athens with the patronage and protection of his one-time student Alexander the Great, Phillip’s son. He then taught in occupied Athens as an “independent contractor” with the occupying force until Alexander’s death made him the target of anti-Macedonian rebels, from whom he fled, dying a year later.

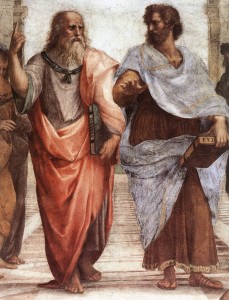

I am thinking about Aristotle this morning — as I am most mornings — because I think he might have something to teach us about the social, political, and economic upheavals coursing through central and Eastern Europe. Aristotle was Plato’s student. Plato was Socrates’ student. And, yet, Aristotle’s response to and diagnosis of Socrates’ trial and death was very different than Plato’s.

Plato, whom contemporary political scientists sometimes label a “realist,” faulted his mentor for, in effect, casting pearls before swine. When he carried his criticism of Periclean Athens into the streets for all to hear, the common people of Athens found his message overwhelmingly offensive. The people of Athens, Socrates told his listeners, had been enchanted by Pericles’ superior command of speech and swindled into entrusting him with their riches to fight wars that were not in the overall interests of the Athenians. Moreover, since Pericles had not given the people of Athens either the wealth or the education to responsibly measure his words, Periclean democracy was in fact a demagoguery, a means whereby a superior power tricks the majority into supporting him. Not religious himself, Pericles used religion to delude the religious and turn them against the openly irreligious oligarchs. No democrat, Pericles used democracy for his own private ends. But to say all of this publicly to the Athenians, thought Plato, displayed a profound lack of wisdom on Socrates’ part; which is why Plato counseled that the wise should keep their wisdom to themselves and should lie to the people for their own good. Plato was a realist.

Plato, whom contemporary political scientists sometimes label a “realist,” faulted his mentor for, in effect, casting pearls before swine. When he carried his criticism of Periclean Athens into the streets for all to hear, the common people of Athens found his message overwhelmingly offensive. The people of Athens, Socrates told his listeners, had been enchanted by Pericles’ superior command of speech and swindled into entrusting him with their riches to fight wars that were not in the overall interests of the Athenians. Moreover, since Pericles had not given the people of Athens either the wealth or the education to responsibly measure his words, Periclean democracy was in fact a demagoguery, a means whereby a superior power tricks the majority into supporting him. Not religious himself, Pericles used religion to delude the religious and turn them against the openly irreligious oligarchs. No democrat, Pericles used democracy for his own private ends. But to say all of this publicly to the Athenians, thought Plato, displayed a profound lack of wisdom on Socrates’ part; which is why Plato counseled that the wise should keep their wisdom to themselves and should lie to the people for their own good. Plato was a realist.

Aristotle disagreed. If only leisured, educated, and healthy individuals could be expected to responsibly govern themselves, then, Aristotle taught, states had a responsibility to make sure that all those who participated in political life were reasonably leisured, educated, and healthy. The alternative, taught Aristotle, was anarchy and revolution.

Since the fourth century, because of his spirited defense of res publica, the notion that citizens of states need to share their common wealth — hence Commonwealth — Aristotle has served as the foundation for all genuine republican political theory. Citizens need to be adequately educated. But they also need to be sufficiently wealthy, leisured, and healthy to rule. States that do not ensure these benefits of liberty invite civil war and collapse. Aristotle knew what he was talking about.

And so we turn to the violence now coursing through central and Eastern Europe. Of course, political scientists and economists of a certain generation came to “pooh-pooh” Aristotle’s “idealistic” prescription for republican health as unnecessary and naive. These theorists and policy makers — not all of whom had been students of Leo Strauss — called themselves “realists” because of their preference for Plato over Aristotle. “Keep your counsel to yourselves and lie to the masses.” That was their advice. Austerity, private enterprise, and an iron fist; that’s the only prescription the people really understand.

And so we turn to the violence now coursing through central and Eastern Europe. Of course, political scientists and economists of a certain generation came to “pooh-pooh” Aristotle’s “idealistic” prescription for republican health as unnecessary and naive. These theorists and policy makers — not all of whom had been students of Leo Strauss — called themselves “realists” because of their preference for Plato over Aristotle. “Keep your counsel to yourselves and lie to the masses.” That was their advice. Austerity, private enterprise, and an iron fist; that’s the only prescription the people really understand.

But, what if Aristotle was right? What if what the people really need is education, leisure, and good health? And what if the austerity measures of the past twenty years have in fact paved the way for the current upheaval? “Well,” say our realist colleagues, “what do you expect from the hoi polloi?”

What do I expect from the people? What do you? It has frequently been said that the people get the leaders they deserve. But, surely, the reverse also holds true. Leaders also get the people that they deserve. And today central and Eastern Europe’s — along with the world’s leaders generally — are seeing the kinds of people their policies have created: hungary, un- and underemployed, in need of good health, in need of better education, in need of more time, more leisure, to consider their options, in need of a safer, more secure world.

These “needs,” as GWF Hegel once taught us, following Aristotle, point to a profound deficit in the theories and policies of the realists we have been following for the past quarter century. Perhaps it is time to once again turn away from Plato and turn toward Aristotle.