It may be inevitable that the subjects covered in my courses provoke reflection among students on the apocalypse. Indeed, one should think that ἀποκάλυψις (ἀπό [away,off] + καλύπτω [to cover]; hence dis-close, dis-cover, reveal) would be among the principle aims of all teaching and learning. Even when students “know” the end of the story, as they do, for example, in ECON 105, The History of Economic Thought, their reflection easily migrates to questions about what is next. That what is next could be a καλυψις or concealing rarely if ever occurs to students, though it is probably more likely than revelation.

And then, of course, there is the natural assumption that we will find what is revealed attractive and welcoming. Were the four horsemen of Albrecht Dürer’s Apocalypse attractive? Were they welcoming? And what about the disclosure announced by their appearance?

And then, of course, there is the natural assumption that we will find what is revealed attractive and welcoming. Were the four horsemen of Albrecht Dürer’s Apocalypse attractive? Were they welcoming? And what about the disclosure announced by their appearance?

Recently a student shared with me an article written by Eric Olin Wright published recently at Jacobinmag.com. The article, “How to be an anticapitalist today,” explores four alternative paths to an anticapitalist future: smashing capitalism, taming capitalism, escaping capitalism, and eroding capitalism. Both the interest attracting readers to Professor Wright’s article and the motivation behind his article could be described as apocalyptic. Professor Wright is seeking to disclose or uncover a different future. His readers would like to discover a path leading to this post capitalist future. Where, in my view, Professor Wright’s article falls short is not so much in the mediations that could plausibly give rise to an alternative, post capitalist future, but the present social mediations that could illuminate these paths. Is there a light that the capitalist social formation sheds on itself, immanent to its own formation, that illuminates the way toward a post capitalist future?

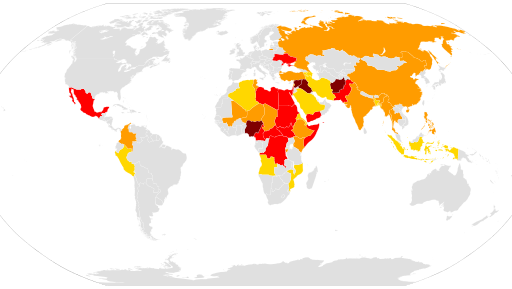

When posed from this vantage point, Professor Wright’s four paths invite us to reflect on the social and historical specificity of each of these paths. Do we live in such a time when violent agents who embrace emancipatory ideals and who enjoy the means for institutionalizing these ideals are in a position to smash and replace capitalism? As I survey the global landscape, it strikes me that the agents who enjoy the means to smash the current institutional arrangements either lack emancipatory ideals (e.g., the United States, Israel, China, Russia) or mistake for emancipatory ideals which are themselves oppressive (e.g., ISIS, al Qaeda, Taliban, Aryan Nation). What can be said about these agents is that (perhaps deliberately) they are both responding to and helping to accelerate systemic dysfunctions and breakdowns from which it is difficult to conclude that emancipatory outcomes will flow.

At first blush, therefore, taming capitalism appears a much more realistic alternative. Here we can identify socially and historically specific conditions — climate change, growing income inequality, racism, nationalism — that are bringing progressive political actors to conceptualize building a more sustainable, perhaps emancipatory, future. There is only one problem: since our social relations are mediated by a social form — the commodity — that derives its value from abstract labour time expended and since the endless production and consumption of material wealth is among the necessary by-products of this form of mediation, it is difficult to identify where and how or when political actors, no matter how progressive, will shift their focus away from concerns over distributional justice and toward the underlying social mediations that give rise both to inequality and to the unending production of abstract value. When, for example, we argue for a meaningful reduction of our carbon footprint, we need to be absolutely clear that the size and depth of this footprint is inextricably tied to a variety of social mediation that produces value as its signal product and material goods only for the sake of this value. Taming capitalism — allowing the logic of capital to persist while regulating its effects — means that the social logic reproduced in commodity production and exchange still forms the guiding structuring principle within society.

Escaping capitalism is non-responsive in obvious ways. And, yet, it still holds a certain attraction particularly for those individuals whose accumulated wealth and value grant them the luxury of carving out pockets of social life mediated and structured (or so they would like to believe) in a post capitalist, emancipatory manner. Even assuming that personal wealth holds the key to personally escaping the mediations that structure social life under capitalism, since these alternative mediations are predicated upon and underwritten by capitalist social forms, they escape with one hand what they restore with the other. This is not to say that this escape might not hold part of the solution to our problem. Yet, on its own, the path it illuminates is the pathway to capitalism, not post capitalism.

Perhaps the most illusory, but for this reason most attractive alternative is eroding capitalism. This, I take it, is the premise of Naomi Klein’s recent cover on climate change: This Changes Everything. Here is the deus ex machina, the environment itself, the material precondition for sustained biological reproduction, erecting its own indomitable barrier to a capitalist future. We can either await the environment’s certain erection of this barrier or we can deliberately chart a course that is sustainable. Either way, capitalism is coming to an end. More modestly, however, this line of argument will be familiar to anyone who has heard or repeated that “Capitalism contains within itself the seeds to its own destruction,” whether in the revolt of the industrial working class, the revolt of the global south, the revolt of the dispossessed, or, now, the revolt of the earth itself. As shorelines retreat and oceanside metropolitan areas sink below sea level, wealth itself may find it expedient to broaden even further the walls separating their air-conditioned luxury from the damp and diseased territories crammed full of the less fortunate. Nor should we anticipate more than terroristic interventions into the peace and quiet of those who can afford climate change. Among the systemic qualities immanent to revolt is the un- or ill-preparedness of those most oppressed by and, therefore, those most motivated to lead their oppressed brethren out of bondage into the promised land. For the fact is that we know of no precedent — 1789? 1848-49? 1914? 1918? 1932? 1949? 1989? — when the oppressed were the architects of an emancipatory future.

But let us suppose that our capacity to produce material wealth has become increasingly attenuated from its foundation in abstract value-creation. And let us therefore suppose that we come to question and politically challenge the legitimacy of the social mediations that perpetuate abstract value-creation: the laws, regulations, institutions, practices, etc. At this point I would argue that two conceits intrude into our apocalyptic rationale. Both are fundamental. First, the conceit that the technology and machinery generating such mountains of wealth are somehow independent from the social mediations upon which such wealth is predicated. So that, for example, as we pivot from a society mediated by the production of abstract value toward a society mediated by relationships among family members, sustaining our physical world, exploring the endless varieties of language, music, and art, it strikes me that we would be foolish not to recognize that the very mechanism generating wealth — the pursuit of abstract value — would without question be a casualty of this transition. A future post capitalist world would therefore of necessity be deprived of some of the efficiencies won through the pursuit of abstract value. There is, in other words, a trade off in this shift of social mediations. We simply do not know what a world would look like that was mediated, let’s say, by familiar and communitarian relations, by care for one another and for our world, by enjoyment of performance, song, art, food, drink and text. The material world — including its capacity to generate material wealth — will be altered as we pivot away from abstract value production.

The second conceit, perhaps even more significantly, concerns the agents of this pivot. The narrative we are inviting social actors to entertain tells a story about the increasingly tenuous relationship between material wealth and value. Automation, mechanization, and robotization are making human intervention into the production process increasingly obsolete. But precisely because this obsolescence is grounded in the relatively greater value produced by shedding human labour, this means that its capacity to produce both value and wealth are predicated upon an ever larger part of the workforce becoming less valuable, socially, than the machines that have taken the place of their labour. Human beings are then compelled to work for increasingly less of the social product at jobs so degrading and demeaning that they are not even suitable for machines. There are some jobs that even machines won’t perform. Human beings locked into such degrading and demeaning jobs almost always find themselves at the bottom not only of the income hierarchy, but also at the bottom of the educational goods market, the health care market, the security goods market, and the family systems market. That is to say, far from being or feeling themselves freed from their compulsion to labour, they instead find themselves bound ever more tightly to increasingly degrading and demeaning labour. Moreover, absent the leisure, health, security, and education that might grant them time to reflect critically on their circumstances, the working poor are also the least likely to recognize or seize the opportunities presented in the isolation of value from material wealth. To the contrary, their very degradation marks them as targets for demagogues pandering to their well-founded fears and pent-up anger. Such are not likely to be the agents initiating the pivot identified above. Rather are the working poor likely to demand more work for more money to buy more things, therein underwriting the social mediations responsible for their own domination.

To find the agents most likely to effect the pivot described above from value production to forms of mediation more appropriate to human dignity, we must instead look precisely to those whose wealth, leisure, health, education, and security have brought the possibility of this pivot to their attention. Clearly this narrative is problematic, not least among progressives, because it does not identify the agencies of the oppressed with the potential for their own emancipation. Rather does it invite the wealthy and, in fact, the extremely wealthy to underwrite a social transformation in which, on some level, they would be net losers. And, yet, at least in my experience, borne out by survey research and voting records, the extremely wealthy are intrigued by their own power to provoke substantive social change. Such curiosity helps explain the large portions of their fortunes the wealthy donate to charitable foundations in general and to educational institutions in particular. Can my wealth make a difference? is a question the super wealthy ask every day. To be sure, the wealthy are not immune to psychopathologies. Rupert Murdoch and the Koch brothers are notorious for their hatred of humanity and their willingness to crush the life out of every living creature that stands in the way of their diabolical dreams. And, yet, for the most part, what the super wealthy lack is not a soul, but a narrative that places them at the center of emancipatory history.

And what might that history entail? It would entail sending the efficiencies seized by the wealthy back down the income hierarchy — not in the form of money, but in the form of health, leisure, security, and education. Spreading these efficiencies downward and outward could hold the promise of helping constitute the possibilities and capabilities that the seizure of wealth has deprived the working poor. Imagine, for a moment, if the same capital investment enjoyed by today’s congressional misanthropes were earmarked for candidates committed to broadening the social franchise of the working poor; expanding their health, leisure, education, and security and therein underwriting their political independence. On some level, of course, this would constitute a regression to the deus ex machina; but here in the guise of a modern-day Rockefeller or Carnegie. Yet, if we believe that even the capacity to think and reason clearly is not independent of the security of our bodies and minds, then it stands to reason that those bodies and minds best able to think for themselves are those that are secure in their freedom.

Clearly what we are talking about here is Class. And the question that we are raising is whether abstract value has so isolated itself from material wealth that historically and socially specific agents can deliberately and knowingly act to transform how our social relations are mediated in an emancipatory way.

I have not thought about Eric Olin Wright, author of the article in Jacobinmag.com, for almost forty years. It was in the early 1980s that I enrolled in Professor Wright’s sociology seminar on Class. His ideas still provoke. Perhaps they also disclose, discover, and reveal.