When students enroll in my History of Economic Thought it is not infrequently the first time anyone has invited them to critically reflect on the social and historical conditions that gave rise to our own, scientific and highly idiosyncratic way of engaging our world. This is because, for the most part, students have naively inherited one of two popular ways of thinking about knowledge: either the scientific method is a cultural preference (as in “western science”), as though points on a compass were somehow constitutive in our preference for the scientific method, or knowledge characterizes a world that is already fully formed but that we, the analytical instrument, only slowly have come to appreciate. Today far and away it is the second, positivist, outlook that prevails.

I invite my students to critically reflect on a somewhat different set of questions. Why is it that capital and capitalism appears to be so tightly bound together with the scientific method? One place where this question looms large is in Carl Menger’s Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaftslehre [Principles of Economics] (1871), whose very first sentence reads: “Alle Dinge stehen unter dem Gesetze von Ursache und Wirkung” [All things are subject to the law of cause and effect] (1), and then goes on to show of civilization itself is grounded in the penetration and expansion of private markets into all corners of human life.

As a people attains higher levels of civilization, and as men penetrate more deeply into the true constitution of things and of their own nature, the number of true goods becomes constantly larger, and as can easily be understood, the number of imaginary goods becomes progressively smaller (Principles, 53).

The quantities of consumption goods at human disposal are limited only by the extent of human knowledge of the causal connections between things, and by the extent of human control over these things. Increasing understanding of the causal connections between things and human welfare, and increasing control of the less proximate conditions responsible for human welfare, have led mankind, therefore, from a state of barbarism and the deepest misery to its present stage of civilization and well-being, and have changed vast regions inhabited by a few miserable, excessively poor, men into densely populated civilized countries. Nothing is more certain than that the degree of economic progress of mankind will still, in future epochs, be commensurate with the degree of progress of human knowledge (Principles, 74).

As investors gain ever more control over all of the factors of production they also gain increasing mastery over how these factors causally relate to one another. Were we not driven to gain command over all of these factors in order to produce ever more refined final products, human beings would have remained “miserable” and “excessively poor.”

The further civilization advances, and the more men come to depend upon procuring the goods necessary for the satisfaction of their needs by a long process of production (pp. 67 ff.), the more compelling becomes the necessity of arranging in advance for the satisfaction of their needs—that is, of providing their requirements for future time periods (Principles, 78).

As soon as a society reaches a certain level of civilization, the growing division of labor causes the development of a special professional class which operates as an intermediary in exchanges and performs for the other members of society not only the mechanical part of trading operations (shipping, distribution, the storing of goods, etc.), but also the task of keeping records of the available quantities (Principles, 91).

I need hardly point out that all these phenomena accompany the transition of mankind from lower to higher levels of civilization. From this it follows, as a natural consequence, that with advancing civilization non-economic goods show a tendency to take on economic character, chiefly because one of the factors involved is the magnitude of human requirements, which increase with the progressive development of civilization (Principles, 103).

Usw., usw. . . . until at long last we are able to throw very small objects at unbelievable speeds at similarly small objects traveling at similarly high speeds separated by millions of miles and enjoy a high degree of confidence that we will be able to land the one on the other successfully: a victory not only for science and capitalism, but for civilization.

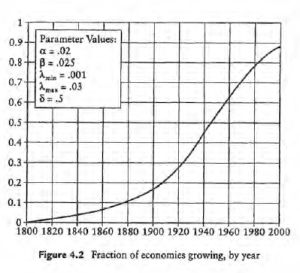

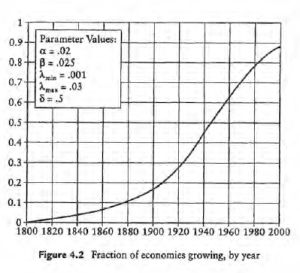

We would like to feel that this story is very old. It is not. As Francis Fukuyama points out, so novel is this story that Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) himself could not crack its code. We had in fact to await Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) to tease out its true meaning. Knowledge and human production progress together showed Hegel, sometimes driven, sometimes pulled by a Weltgeist a “world spirit” whose end would be comprehensive, universal, rational integration of all being and knowledge in a singular totality. Which two centuries later will yield the smooth growth curves produced by the University of Chicago’s Robert E. Lucas, Jr.:

Proof that knowledge and capital march in lock-step.

Which makes Carl Menger something of a prophet, nicht war? We will see. But what is most disturbing for many students to Carl Menger’s argument is that it shows the tight connection between knowledge, what we know, and how we engage in the material world, what an older generation of economists might have called “modes of production.”

Carl Menger would like to believe that the capitalist “mode of production” lies dormant just beneath the skin of every hominem, however primitive, that has ever walked the earth:

Even at the lowest levels of civilization we encounter a certain amount of knowledge of the available quantities of goods, since it is evident that a complete lack of this knowledge would make impossible any provident activity of men directed to the satisfaction of their needs (Principles, 90).

From year 1 human beings have been straining to become what we are. Since 1871, of course, anthropologists have conclusively shown that being “us” was the last thing on anyone’s mind for the past 2.4M years, that being “us” only first occurred to anyone most likely no earlier than the fourteenth century (N Bird-David, “Beyond ‘The Original Affluent Society'” (1992); J LeGoff, Time, Work and Culture (1980); D Landes, Revolution in Time (1983); EP Thompson, Customs in Common (1991)). And, yet, as F Fukuyama brilliantly illustrates, the myth of our immanent, long-expected arrival since the beginning of time persists even among very smart people.

True. Carl Menger believed that scientific economists could assist this process by excluding what he called “imaginary goods” — e.g., “medicines for diseases that do not actually exist, the implements, statues, buildings, etc., used by pagan people for the worship of idols, instruments of torture, and the like” (Principles, 53) — from their models. The more scientific their own outlook and models, the more accurate would their results prove. And, yet, even here C Menger was not too far off. Even if capitalism has not led to the end of magical thinking, superstition, and spirituality — all of which have blossomed under capitalism — religion in a far older and fundamental sense is quite dead. Religious practitioners no longer feel obligated to orient their bodies whether by the compass or between heaven and earth. Nor do they take changes in weather, seasons, or migration patterns as signs from a benevolent God that they should plant or harvest, fish or pull up anchor, or rest for a season. Just as they no longer interpret deforestation, the disappearance of game, the spoiling of a water source, or other forms of environmental degradation as signs of divine wrath.

This is the flip side of comprehensive, total, rational integration of all things; the flip side of bending all social and physical reality to the one end of production for pecuniary exchange. For it so happens that in most respects these “barbarous” “primitive” communities were far better attuned to the physical world about them than we ever will be. So much so that now that we have bent all social and material facts to serve this one singular end we no longer grasp how or why else the world might exist. Which in the end might prove our final undoing, n’est ce pas?