In his Introduction to Capital, Karl Marx offered an observation that may seem trite:

Exchange-value appears first of all as the quantitate relation, the proportion in which use-values of one kind exchange for use-values of another kind. This relation changes constantly with time and place. Hence exchange-value appears to be something accidental and purely relative. Consequently an intrinsic value, i.e. an exchange-value that is inseparably connected with the commodity, inherent in it, seems a contradiction in terms (K Marx Kapital I:49-50).

Herein Marx speaks to a common misunderstanding about value. For, even though it has formed the centerpiece of neoclassical economic theory since 1868 (at the latest), value is still poorly understood even by some economists.

That misunderstanding arises from the two-fold character of the commodity, including the labor commodity, which, on the one hand is what it appears to be, however culturally, socially, or historically embedded. It is some thing. And we value every thing for the qualities it enjoys — again, however culturally or historically inflected — that satisfy some need. So, for example, the value a relic has for me is found in the actual hair, bone, skin, fabric of the relic, which are themselves embedded in a culture and along a historical path in which such things are valued. In capitalist societies, things are also related to one another by a common, shared, universal element — value — that each thing bears not because of the specific, individual qualities any thing enjoys, but on account of what they all share socially.

The social character of value has led many people to conclude that value is arbitrary or conventional. The value of any thing is wherever aggregate supply and aggregate demand intersect. Constrain supply holding demand constant and the value of any good will increase. Expand supply holding demand constant and the value of any good will decrease. Or, culturally, expose enough of the public to a wildly popular movie — for example, the Matrix — and then watch how fashion choices marginally shift. This could suggest that value is totally arbitrary or conventional.

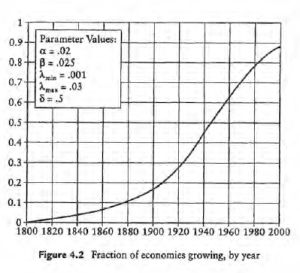

Value is specially confusing when we consider how it is shaped by automation. Obviously investors will only automate when the marginal returns they anticipate from automation exceed the marginal returns they derive from manual or semi-manual forms of production. In the real world, where millions of commodities compete for total aggregate income, few commodities enjoy the capacity when automated to shift total demand. There are, of course, exceptions. Because petrol is generally considered among the least elastic commodities, when fuel prices rise, consumers are inclined to spend less on other, more elastic goods. In theory, however, we can easily appreciate the conditions under which automation might actually lead to an aggregate decline in marginal returns.

Take a factory that relies upon human labor. Employees at the factory are compensated for their labor with a wage, a portion of which they spend on goods, perhaps the goods that they help manufacture. Assuming for the moment a closed system, where aggregate supply exactly equals aggregate demand and where the total value of all goods produced equals the wages consumers are ready to spend on these goods, any decline in wages is matched by an equal decline in the value of the goods for sale. So, for example, if the total of all goods is an apple and the sum total of income is $1, which the consumer has earned picking apples, automation of apple picking must consider who will purchase the apple once the apple picker is made redundant. If total income in this market is reduced to $0, then the value of the apple cannot be greater than $0.

Now, however, let us suppose that we add another manufacture — maintenance of automated apple picking machines, which farmers hire at a wage greater than the manual apple pickers. If apples nevertheless remain the only good for sale, at $1, I will still not automate, since I must still compensate my technician at least $1 if he is to purchase my apple. But let us suppose that automation decreases the cost of picking each apple by 50%. Now if I compensate my technician at $1, his wage remains identical; and yet its marginal value, relative to apples, is now 100% greater since he can purchase two apples with it. Automation has doubled the quantity of goods, holding value constant. Efficiency has doubled utility or use value. Measured in dollars, we still have x dollars worth of apples equals x dollars in total wages; but, x dollars in wages now equals two apples.

In the real world, where hundreds of millions of goods are consumed, and where investors must decide whether or not to automate a process, investors are deeply interested in aggregate demand. Should innovation give rise to a decline in aggregate economic growth, then investors will want to know whether and by how much a marginal decline in aggregate demand will place downward pressure on their marginal returns. We saw in 2006 how a dramatic decline in aggregate value placed the jobs of millions of manufacturing workers in danger. For investors, the question was not whether Ted, Susan, and their family could meet their mortgage payment or pay for Jimmy’s anti-epilepsy medication; the question was the bite declining wages would take out of aggregate consumption for all goods.

The misunderstanding is . . . understandable. We want value to reside in things, which is precisely how classical economists such as Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Thomas Malthus understood value. Whether they were calibrating the value of things to labor time (A Smith) or to the relative value of the things out of which other things were composed (T Malthus) or, even, straining toward a new, more dynamic expression of value (D Ricardo), classical economists wanted value to reside in things.

Neoclassical economic theory, from this vantage point, appears incoherent. For it measures value according to its market value — value is whatever a good or service or idea commands on the market. This market value is its objective value.

To further complicate matters, market value is always hedged in, constrained and channeled by a bewildering variety of factors that we can summarize by law, custom, regulation, and habit. So, for example, a private investor who enjoys access to a lawmaker might make it advantageous for that lawmaker to pass a regulation that increases demand for his good while decreasing the demand for his competitor’s good; or a reliquary might claim a monopoly over the sale of candles and deny common candles access to its sanctuary. These constraints are literally innumerable and yet clearly they shape the values of goods traded even in the most liberal of markets.

It may appear a giant leap, but the question of value and its significance reappears every time we appear on the verge or even in the middle of an efficiency-rich technological innovation. This is because, in the short run, marginal efficiency is measured by the cost entailed in producing any good over the quantity of goods produced at that cost. In the short run, private investors will only replace human labor with technology when the cost of that technology per unit produced is less than the cost of the labor it displaces. The result, on its face, is a drop in the value of the labor relative to the technology, which are marginally identical — identical at the margins.

Notice that were marginal demand for a good reduced by an equal or greater amount than the efficiencies generated by the new technology, the value of that technology would not be greater than the human labor it replaces. So, for example, did adopting a technology reduce employment and wages sufficiently to shift demand for that good downward beyond its marginal utility, an investor would still not adopt the technology. Only if the marginal cost were sufficiently reduced to also lower the price of that good and increase demand up to the margin (expanding profits by expanding the demand for goods that bear a lower price), only in this case would investors adopt the technology.

But also notice that significantly lowering the price of a good through technological innovation (in a competitive market) also reduces the marginal profits that might be won from that good; this, in turn, would trigger a realignment of capital investments toward goods with a larger profit margin. So, for example, if automobile manufacturers cannot make sufficient marginal returns because innovation has lowered the price they can command for a good, investors will redirect their capital to niche markets that enjoy higher marginal returns.

Finally notice that this shift in the indifference curve can also be effected by changes in law, regulation, custom, taxation, and so on. So, for example, when Congress deregulated financial markets in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, it obviously increased the attractiveness of financial instruments. The same overall effect was achieved, however, by dramatically lowering taxation on wealth. In both cases, we can observe a shift away from manufacturing and towards capital goods.

Obviously, we could expand these examples indefinitely. But my point is that these basic principles have been well known at least since the 1860s and have not really been in dispute, at least since the 1930s. Value does not reside in things. Regulatory, legal, social, political, regulatory and cultural forms shape and shift value.

We invest in technological innovation even when it displaces labor and places downward pressure on wages only when we can see higher returns from that investment. Which brings us to Larry Elliot’s observation:

Robots will create more jobs, but what if these jobs are less good and less well paid than the jobs that automation kills off? Perhaps the weak wage growth of recent years is telling us something, namely that technology is hollowing out the middle class and creating a bifurcated economy in which a small number of very rich people employ armies of poor people to cater for their every whim.

But automation could only achieve this outcome were it not dependent for increasing marginal returns upon the wages of the middle class. At the very least, this means either that demand for a good — however manufactured is inelastic — or that marginal returns are no longer dependent upon middle class wages and consumption. In the first case, automation increases marginal returns because irrespective of their wage, consumers will nevertheless purchase the good. So, for example, even though under conditions of high unemployment (or stagnant wages) necessities such as petrol will consume a higher proportion of an unemployed person’s wealth — increasing its value to them — they will nevertheless consume a higher value of petrol than they did when they were employed (or earned higher wages). Automation may have some effect on value, but only marginally. In the other case, where marginal profits are independent of the wealth of the middle class, the shift in consumer markets tells us less about how a good was produced — automated or manually — than how wealth is distributed. This is less a consequence of automation than regulation.

We can see this relationship most clearly in the World War II and post-World War II labor and consumer markets. High taxation on profits and wealth